When do you have enough data to start your analysis?

The more data you have, the less likely it is you'll have the time to analyse all of it, especially with looming university deadlines in mind.

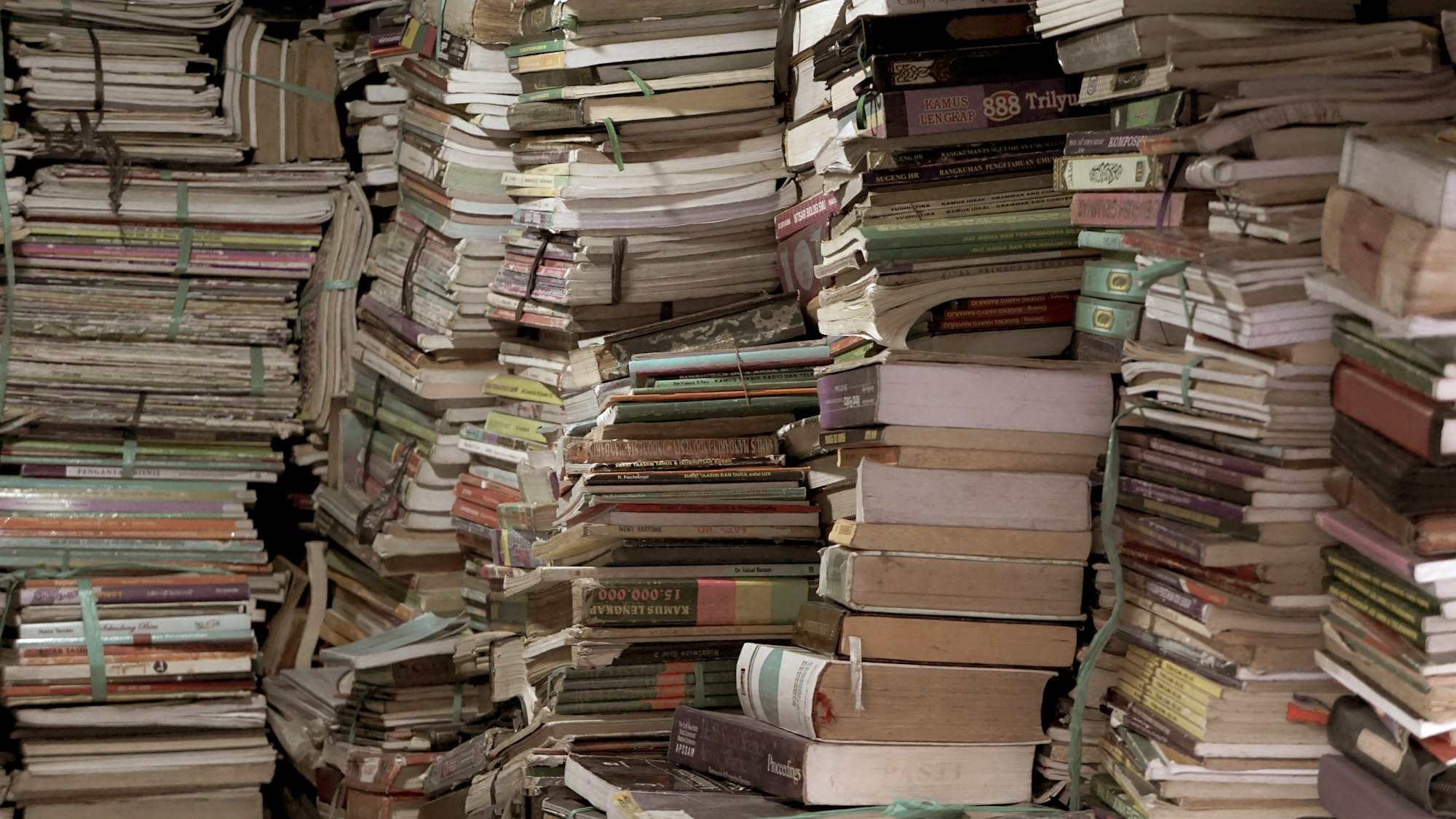

When I was a student, I found it tricky to manage big qualitative research projects with lots of text to analyse. I might have hundreds of pages’ worth of novels, or thousands of free-text responses from surveys. It was hard to look at all that data and not feel overwhelmed!

In those conditions, it was inevitable that I'd procrastinate on my analysis. Moving from data gathering to data analysis was always a trouble, and I'd often find myself twenty-four hours from the deadline, speed-drafting my essay at the same time as doing my analysis and hoping for the best.

In retrospect, I think this procrastination was the result of two things: underconfidence, and not approaching large datasets in the right way. I didn't experience as much friction trying to analyse smaller amounts of data – as a literature student, this was mostly poems and short stories for me, which came much easier than thousand-page Victorian novels. I think this is because it's (usually) feasible to analyse the whole text at around the same level of depth before the deadline, so it's easier to feel confident that you've covered everything.

But the more data you have, the less likely it is you'll have the time to analyse all of it, especially with looming university deadlines in mind.

So, how do we strike a balance? How do we deal with large datasets where we need to make decisions on where our focus should lie? I think some of the stress around this analysis can be reduced by accepting two truths:

- If you're worried about whether you have enough data, you probably already have enough to start your analysis.

Your worry about having 'enough' data comes from a positive place, in the sense it likely means you're thorough and you care about delivering high quality scholarship. But this worry shouldn't direct your subsequent actions. It's your guide, not your boss.

2. Committing to analysing less data sooner will make your analysis better.

Remember that no piece of research or analysis is exhaustive, and that’s a good thing. You don’t have the entire weight of the world to carry with your one research paper. For now, you just need to move things along by an inch. This mindset can help address the problem of thinking you need to analyse all the data, and not just the small portion that will produce insight to move knowledge forward by a little bit. And, you're likely to make a more interesting claim by narrowing your focus, because your understanding of that small piece of data will be deeper.

In the rest of this blog post, I want to help build your confidence to start your qualitative analysis early and reduce some of the stress around the analytical process. I’ll talk about why you should start deep-diving into your data sooner than you think you’re ready, and then, in an upcoming post, I’ll discuss some practical tips to help you get your analysis done and your essays out with less of a struggle.

What are the benefits of starting your analysis ‘early’?

You will spend longer looking at the data in depth.

When I used to work with large amounts of data, I’d spend weeks poring over my data to identify as much usable content as possible, but my analysis ultimately suffered as a result – I didn't have enough time to achieve sufficient depth. It became a vicious cycle that reduced my confidence.

You may feel worse about closely analysing large amounts of data because it feels like you're not seeing the forest for the trees, or like it takes away the time you need to find every relevant snippet of evidence for your argument.

However, qualitative analysis is an organic and iterative process. Commencing more in-depth analysis does not mean that you have to lose sight of the bigger picture. In fact, you can continue to skim through a larger sample of data as you begin to extract insights from the piece you’re closely analysing – and the close analysis will hone your instincts for other pieces of data you might want to save and review later.

You also don’t necessarily have to stop gathering data to start analysing, especially not for purely qualitative projects. By going in-depth early, you'll be able to identify where future pieces of data fit in with the whole, and whether they're relevant to your argument.

In short: starting your analysis is not closing a door; it’s opening one - one that may in fact lead you back to other parts of your data, and allow you to make increasingly more useful connections and insights.

You have a chance to play with all your ideas, no commitment necessary.

Starting early - and small! - means you have less of a need to immediately commit to a research topic, and can spend more time exploring your ideas. Close analysis will help you to narrow down those ideas and find the one that draws your interest the most, or that appears to be the most convincing.

If you have a few ideas but you're not sure which will be best, try taking a small extract from your data – don't think about it too hard; just pick one that jumps out at you. Go through the extract and analyse/code it several times, and each time change the topic idea or research question you have in mind. It’s likely that one will feel the most natural and produce the most interesting insights. From there you just have to trust and follow your own curiosity and see where the topic takes you!

You won’t have time to get attached to a hypothesis that turns out to be wrong.

By starting your analysis early, you will quickly get a sense of the concrete evidence you have to support your argument. You will test your claims quicker and be able to alter your thesis statement before you run out of time. This reduces the pain of coming up with a brilliant hypothesis in the data gathering stage… only to find out there’s minimal data to support it for the length of the paper you're writing, or the data is in a different context than you remembered, making it unusable.

You will immediately know if you do need to prepare more - and you'll have the time to fix it!

Sometimes the best way to test whether you're prepared is to just set off and see how far you can get. We’re not launching a rocket here. Being underprepared isn’t going to be catastrophic. You are likely working on a computer with automatic backups, version history and an undo button. You’ve got all the elements in place to reverse your choices and reassess if you find yourself on the wrong path. (And if you're using software like Quirkos to organise and analyse your qualitative data, you'll also benefit from autosave and, with our Cloud plan, automatic cloud backups!) Because you started early, you haven’t put in a ton of time and effort into carving out that path only to find you can't find your way back to the start in time for your deadline. The work here is very rarely wasted: setting off on the wrong path still does the work of ruling that path out, and starting the close analysis will help you to find the specific gaps you need to fill in your understanding or data.

And, while we're talking about identifying gaps in your research...

It's methodologically sound.

In the context of qualitative research methods, many methods (including grounded theory, reflexive thematic analysis and constant comparative method) recommend starting your analysis during the data collection process. This can increase the validity of your results by immediately highlighting gaps in your participant sample or methods of data collection. By analysing early, you can address these problems before it's too late, and help avoid locking yourself into a conclusion that's limited by the range of people represented in your sample, or by the few comments you have available. Starting early means you have the time to change up your recruitment strategy, carry out follow-up interviews or tweak the questions you're asking your participants to gather more comments on an area of interest. It gives you flexibility in your method to adapt when things don't quite turn out as planned.

You will naturally develop a tight focus for your paper just by starting early and selecting a start point.

When I was studying for my bachelor’s in English Literature, the analysis I did for my essays wasn’t really ‘analysis’ at all. I would type up hundreds of pages' worth of quotations and extracts, dutifully copying across the formatting and italics. And then, after all that effort, I'd be two days from the deadline with no writing done. I’d frantically pull together an essay plan with my raw quotations and write the analysis around an argument based solely on the vibes I had accumulated while typing things up, usually while watching Netflix in the background. You can imagine that it was pretty difficult to come up with an argument and the supporting evidence and analysis in two days, while I hadn't been paying close attention while rereading and typing up the texts. Data collection and organisation felt like a waste of time, and essay writing felt exhausting and stressful.

It would have been much easier if I’d started that process sooner and followed my nose on the parts of data that seemed the most promising at the start, rather than thinking I needed to achieve the same amount of analytical depth for an entire 400-page novel.

Remember that if the amount of data you have left to analyse feels overwhelming, this can be the result of the sunk cost fallacy, where you’re trying to make use of everything because you went to all the effort to collect it.

So, how do we get out of the vicious cycle of sunk costs? Look out for Part Two of this post, where I will share some techniques that will help you get closer to your data faster!

Be sure to check out Quirkos, our software which is designed to keep you close to your qualitative data while undergoing analysis and writing up! Make use of memos to reflect on your experiences, use our chat function as your own private journal, and use categories and subcategories to highlight areas of interest in qualitative texts to help you narrow down your focus.