The uses of Memos and Notes for analysis in Quirkos Web

There is more to analysing data than coding and labelling it. Analysis comes from thinking about your data. Our most immediate thoughts are often fleeting, random and we don't want to lose them. So we create a memo. If you want to know more about analytical uses of memos and notes, read on.

There is more to analysing data than coding and labelling it. Insights emerge when you look at that coding and examine data for patterns. But the real analysis comes from thinking about your data, and collating and organising those thoughts. We may enable this thinking by talking to others or even performing our thoughts, but most commonly we will write. Our most immediate thoughts are often fleeting, random and in direct response to something specific we have read in the data, and we don't want to lose them. So we create a memo. (If you want to know how to create memos in Quirkos, go our How to use Quirkos page, but if you want to know more about analytical uses of memos and notes, read on.)

If your data is on paper, such as a transcript or a publication, you might write in the margins of the page. This is why you might hear memos being called marginal notes. You may even deliberately double-space the text in interview transcripts so that you have space to write your comments directly into the transcript. Or maybe you like sticking notes onto the page, with sticky notes. Word processing apps allow you to insert comments, which can be shown or hidden as you prefer. Computer Aided Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS) like Quirkos, also allows you to make notes and comments to capture those fleeting thoughts in ways that are closely associated with the data.

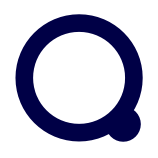

Quirkos keeps it simple. Quirkos only has one specific function for adding memos. But before you scoff that CAQDAS X has loads more functions and buttons for adding different types of memo or annotation, let me show/explain the benefits of having just one specific function. Then I'll show you how Quirkos has actually got more ways for you to create and use memos. I'll be using data from our Qualitative Researcher Journeys project.

Just one memo 'button'

Just one button, no worrying whether you've pressed the wrong button, or whether it's the 'right' type of button. Maybe I'm a slow learner, but it took me ages to grasp the difference between a memo and an annotation in NVivo, so just one button is great for me.

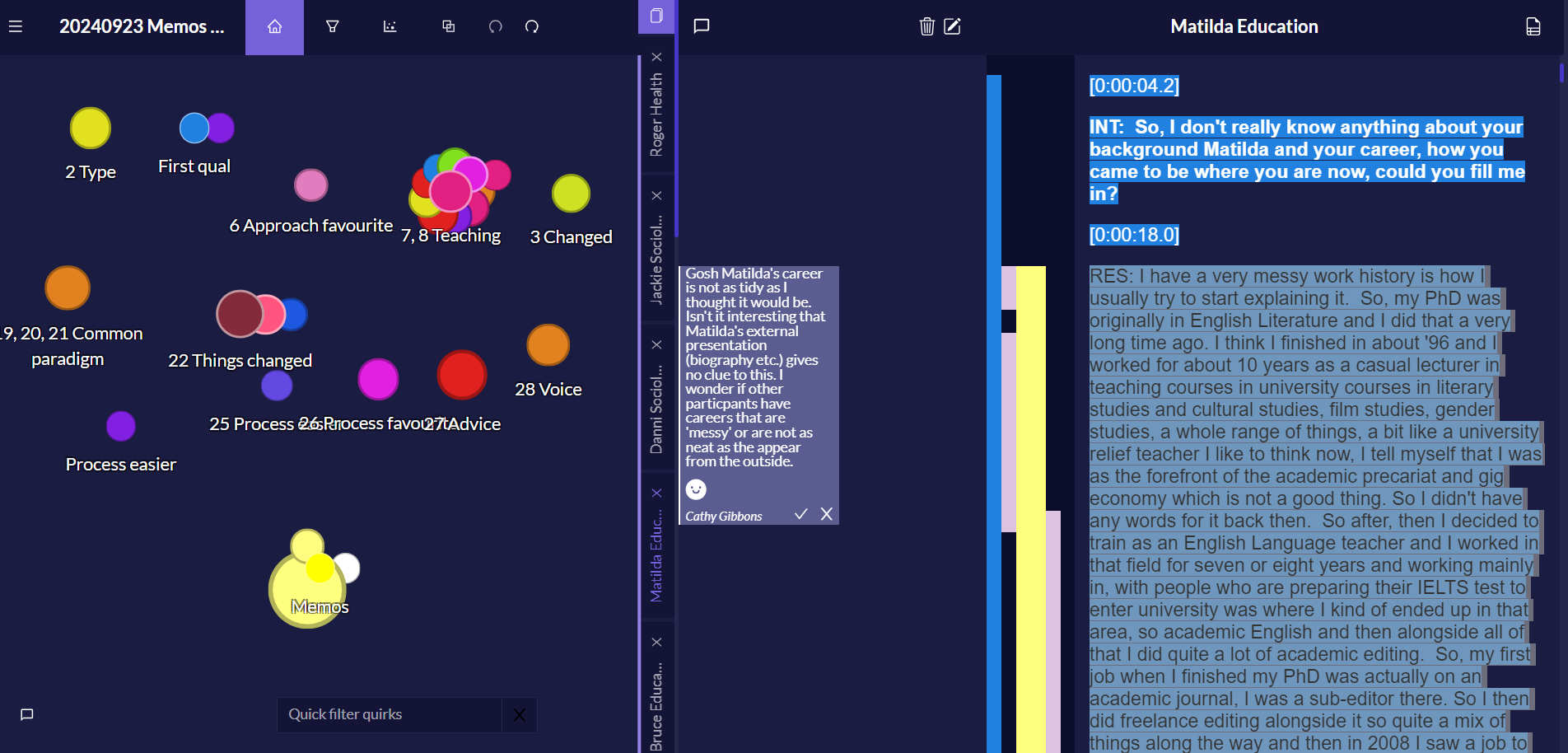

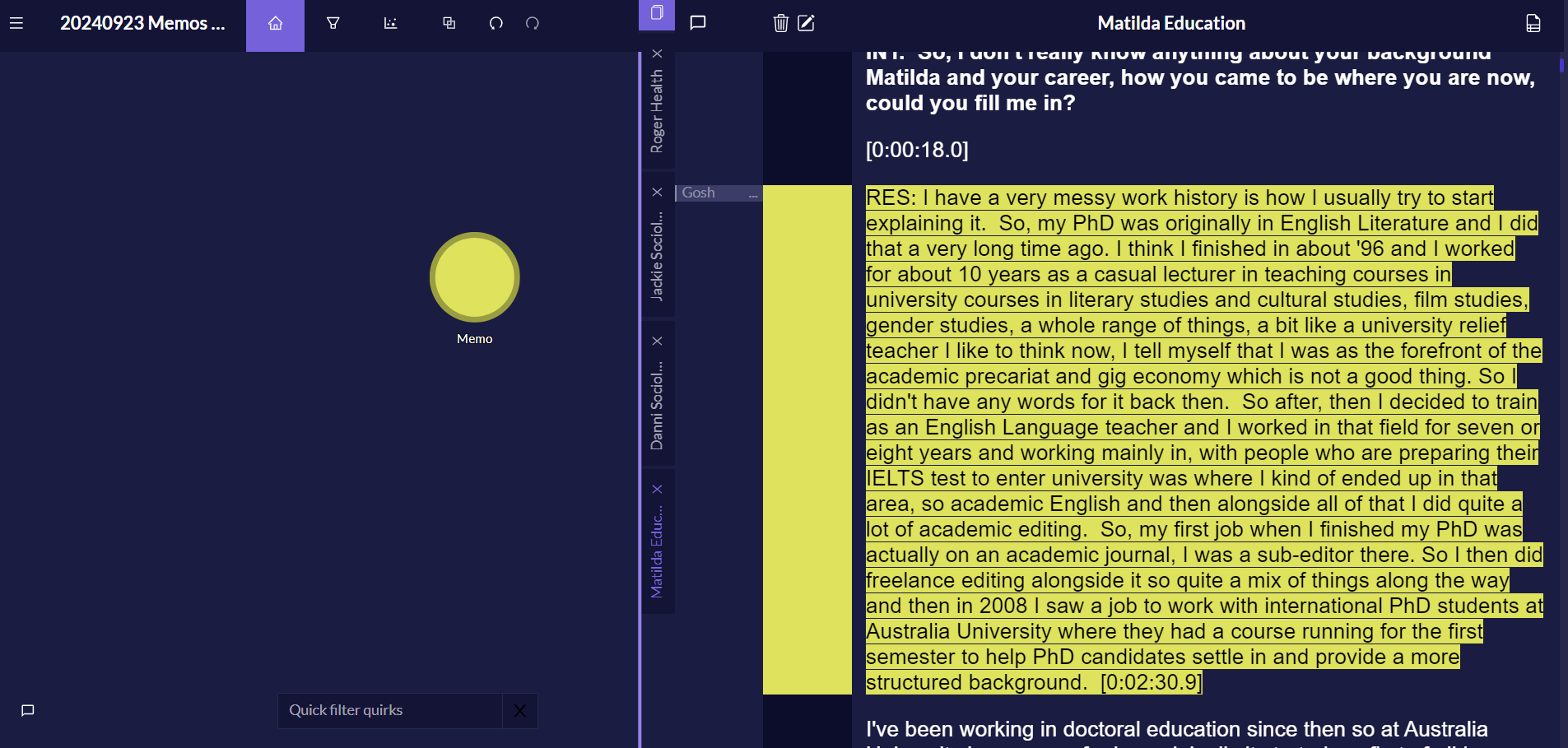

In the example below you can see I have made a note in the memo (middle) column relating to my choice of coding in the interview transcript text, and my rationale for that choice.

"Gosh Matilda's career is not as tidy as I thought it would be. Isn't it interesting that Matilda's external presentation (biography etc.) gives no clue to this. I wonder if other particpants (sic) have careers that are 'messy' or are not as neat as the appear from the outside"

You can tell that it's quite informal, but it tries to give enough context so that I can understand it when I come back to it later. You can add as many memos as you like throughout your sources.

Using memos instead of coding

Quirkos aims to be methodologically agnostic. This means that you apply your thinking to the project in any way that you want to. This includes the option to NOT use some of the tools, such as the Quirks for coding. It can be argued that creating codes is un-necessary (see NOT Coding qualitative research and delayed categorisation), and that it is all too easy for the inexperienced to go no further than data-labelling when applying codes. Instead of simple labels, you might prefer a way of capturing your analytical thoughts as you listen, read and reflect on the recordings and transcripts.

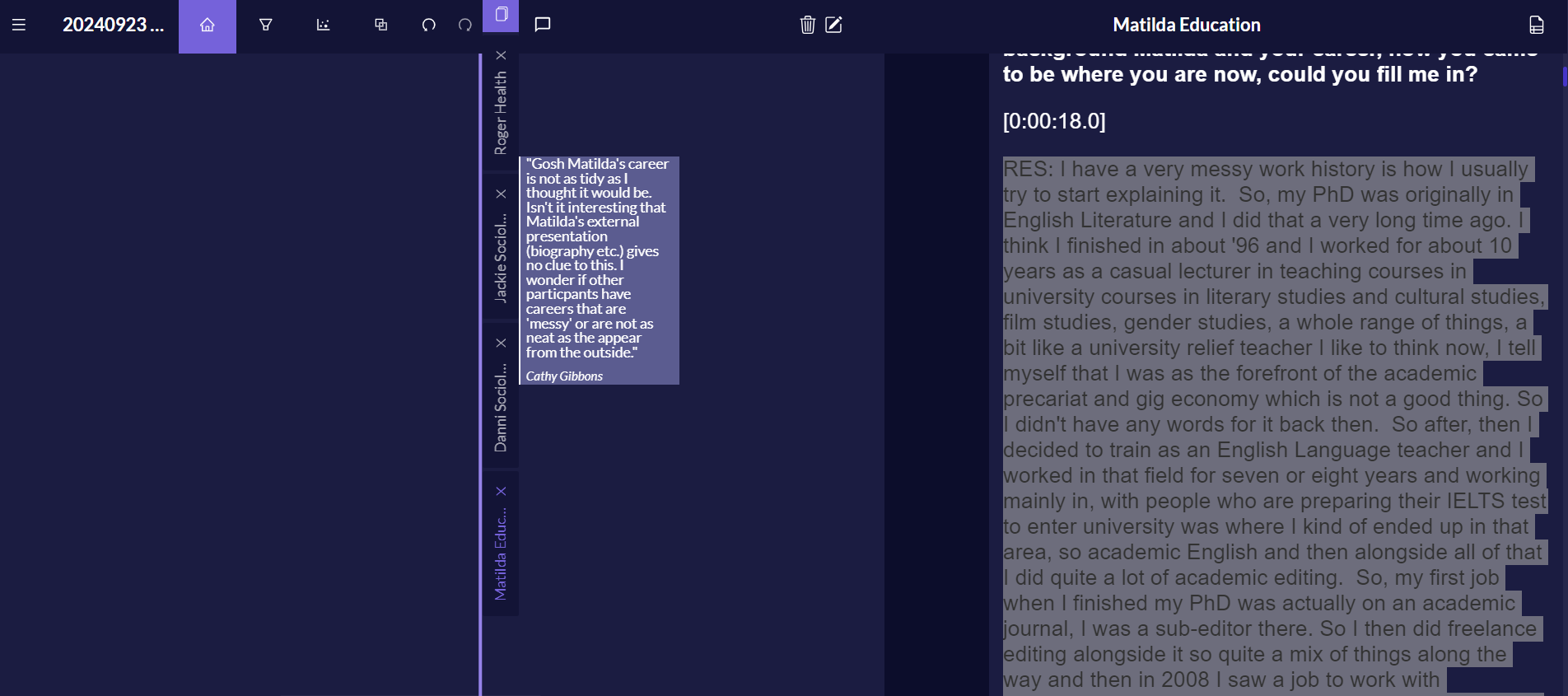

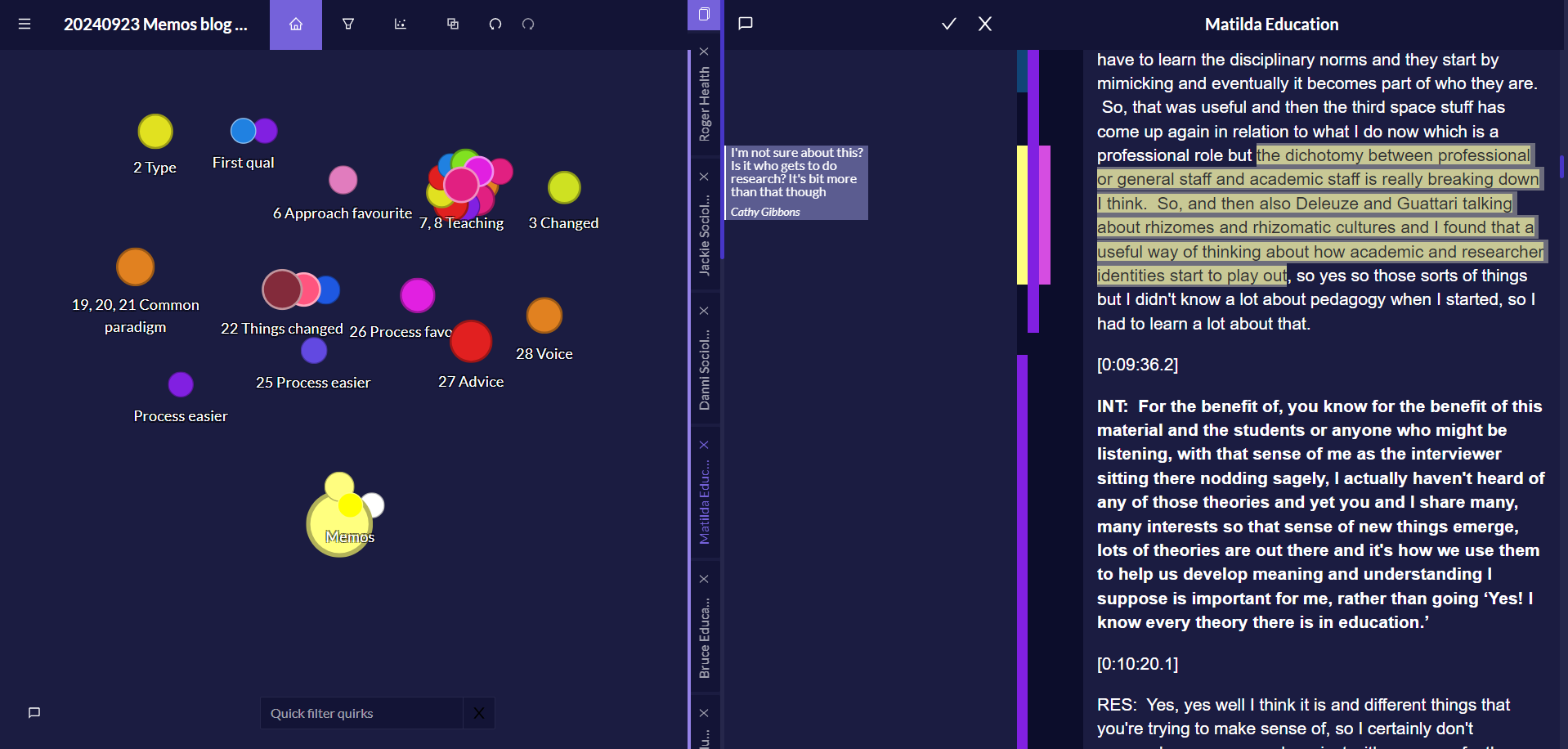

You can use the memo function for your comments, notes, reflections, observations and so on, as shown above. Or just use the transcript itself. In Matilda's transcript below I have inserted my comments directly into the transcript, rather than in the memo column. (I always make my inserts italicised and underlined to avoid confusing my notes with the research source).

"Gosh Matilda's career is not as tidy as I thought it would be. Isn't it interesting that Matilda's external presentation (biography etc.) gives no clue to this. I wonder if other particpants (sic) have careers that are 'messy' or are not as neat as the appear from the outside."

I have noted what is interesting about the paragraph AND added a potential question. "I wonder if..." indicates that I need to follow-up by comparing Matilda's experience with other participants. This is analytical: I'm looking at patterns and making comparisons in order to develop insight, conclusions and findings. I could also add a reflexive memo on my own career and how this might influence my own perceptions of research careers or my participants', and so create a greater understanding of the context of my relationship with the data.

You can add the annotation anywhere you like (such as mid-sentence) and it has the advantage of remaining in context. To find it, you need to read the text and reading the text is vital to keep your analysis contextualised. (You could use a simple word search too).

Other ways of creating immediate thoughts could include using the chat function (see bottom left of the canvas). Whilst this is often used for chat between group project members, you can use it for instant reflections on the whole project, as it is not connected to a specific part of the data. Similarly you could create a source and call it 'Memos' and use it like a notebook for your passing thoughts, and even code them later. These tools could work for you, as they discourage mindless labelling, and an intense relationship with the data is required for you to retrieve your work and understand the indirect relationships across cases.

Connecting your thoughts directly to the data

One of the advantages of writing a marginal note or adding a sticky note on to the page is that you can see exactly which data your thoughts are connected to. You can enhance your ability to see possible analytical connections between memos by coding your memos.

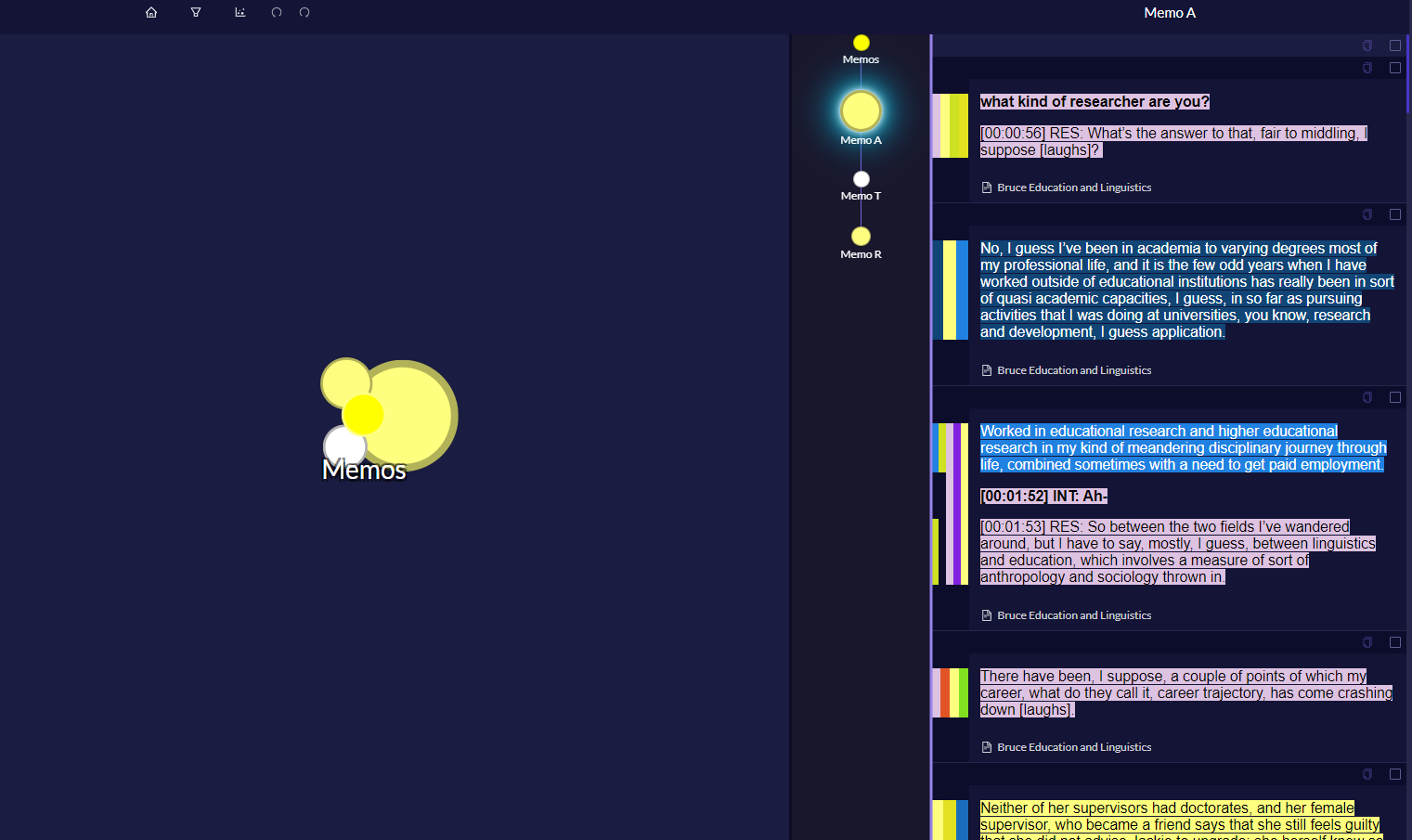

Create a quirk for your memos

If you code the text associated with your memos to named Quirks (I've called mine Memos) you can see where in the different sources memos have been made. You can also see if you have made any other coding associated with the memoed text. No CAQDAS software can tell you the significance of these connections, but by seeing them you can begin to ask yourself the 'So what?' question.

As you go through your data you may find that having lots of unstructured memos doesn't suit you, and you'd like to impose some order or analysis on your fleeting thoughts, or ways to retrieve them in a structured search. Gibson (2007) and Barbour (2014) recommend that you do impose some kind of order on your memos. When you impose this order is up for debate, but you will probably have a small number of different types of labels for your memos from the outset, such as things that relate to the research process and analytical thoughts. (You can discover more about categorising memos on our curated course.)

In the Qualitative Researcher Journeys project I created just 3 different types under a main heading of Memo. I created Quirks for them so I could find them more easily in the data, and see how they are linked in the data to other codes.

Memo A - Analytical memo -anything related to analysis, including 'first pass' coding.

Memo T - Technical memo - especially around the tools used. Not research process.

Memo R - Research Process Memo - including interactions between the Interviewer and respondent.

Once the text associated with the memo was coded I could see that the coded text is yellow to match the Memo A Quirk. I could also see the other coding associated with Matilda's transcript text by looking at or clicking the coding stripes.

Retrieving and searching your memos

It's perfectly valid not to use quirks to label/code your memos, and as Daniel discusses in the blog NOT Coding Qualitative Data, and Delayed Categorisation, it has advantages. However it makes searching and retrieving your data both laborious and time-consuming. Often CAQDAS, is designed specifically to quickly search and retrieve coded source data, not specifically memos. So, how you decide to work with your memos in Quirkos could well be affected by how you want to see your memos in Quirkos outputs.

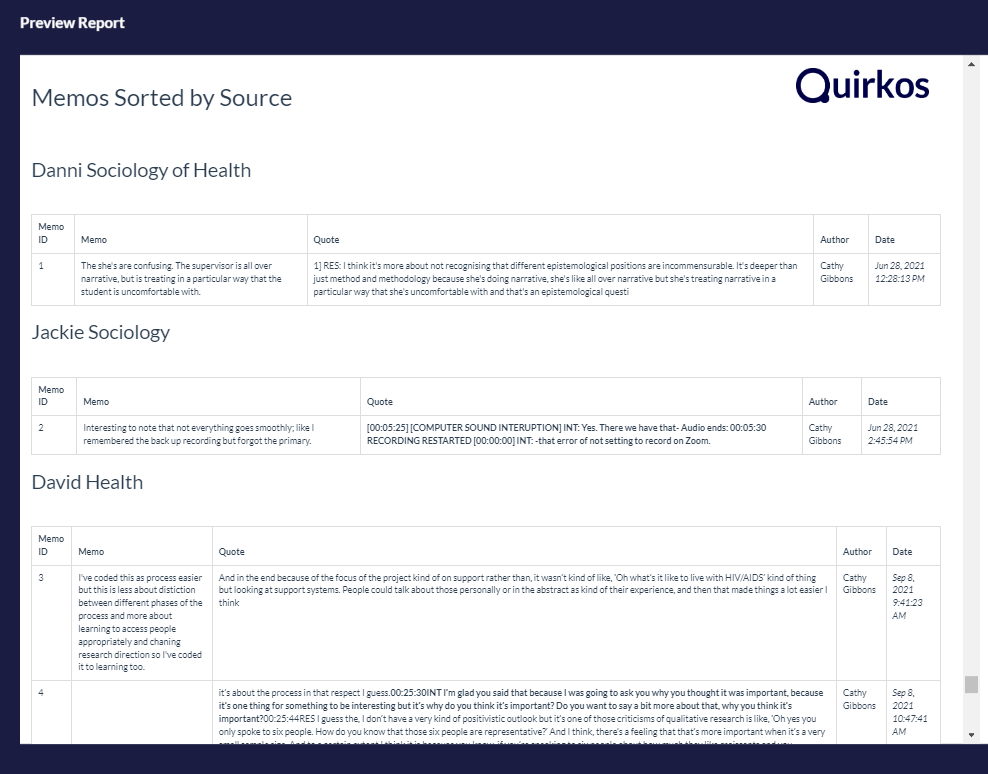

Quirkos outputs for memos

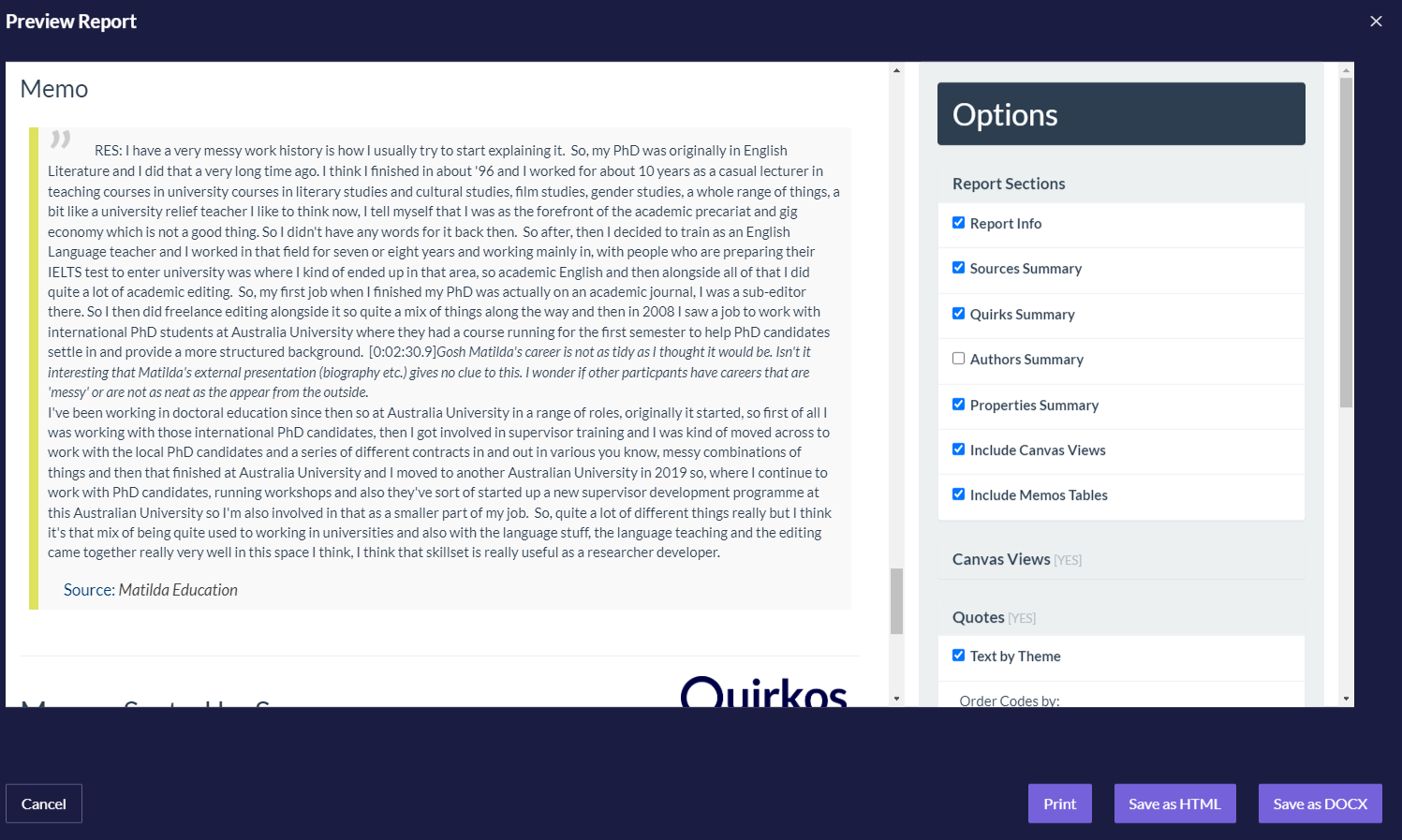

You can export a formatted version of your data as a report. Here your Memos are automatically connected to the original source data in table format. You can see all your memos (and export them) in their original context i.e. connected to the source data. Each source is presented in turn. So, if I want to see all of the memos for a particular persons transcripts, this is very helpful. This report could be an end in itself, but more usefully you can use it to stimulate thought and ask more questions of your data AND your analytical process. I can see below that Danni and Jackie have only one memo each, and David has more. Why is this? Do I need to go back and look more carefully at Danni and Jackie? What is the nature of the David's multiple memos? Are they truly useful thoughts or fleeting notes that no longer seem relevant? Only the researcher who is deeply familiar and involved with the data can answer these questions.

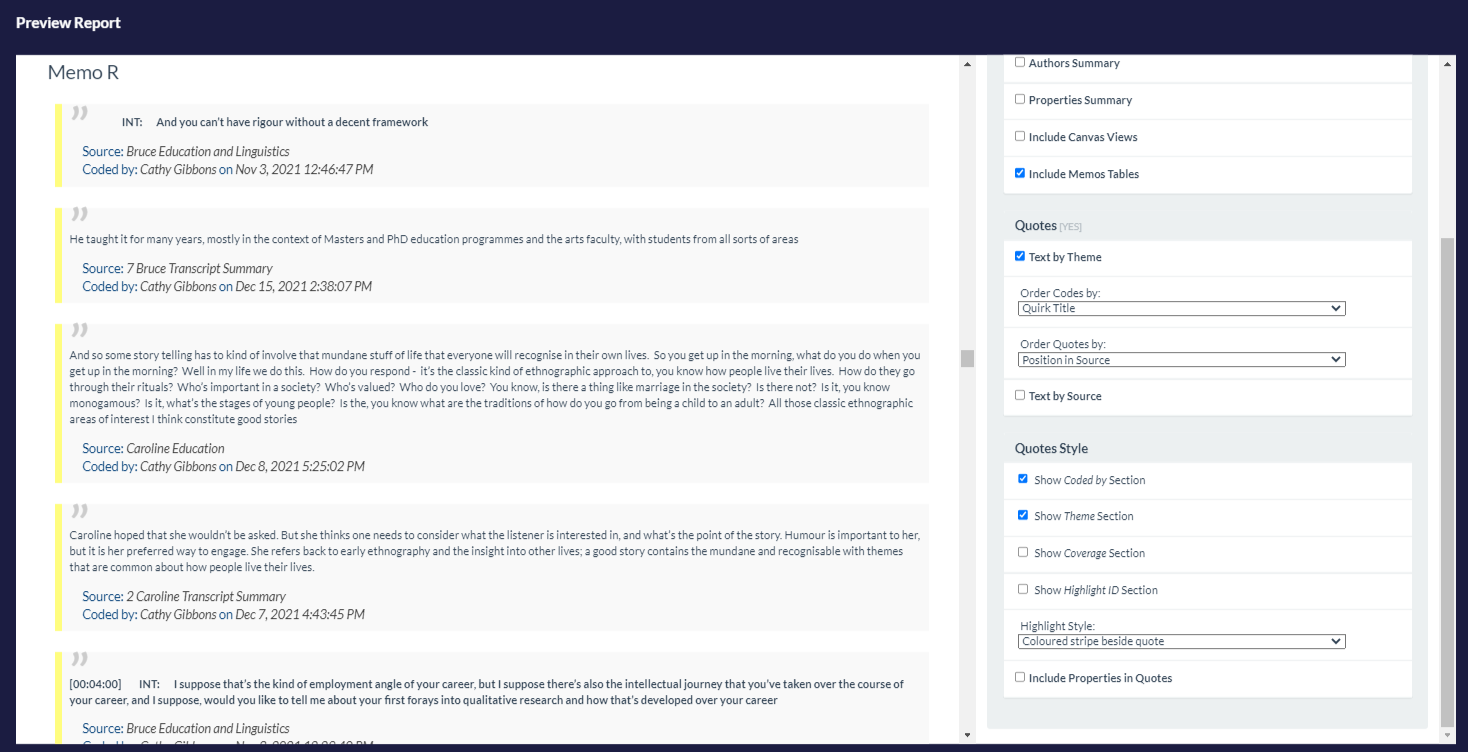

If you created any codes for your memos, you can see the data from all sources attached to a particular code. Now you can see the source data from across all the sources, gathered under a particular memo code. In the example below (Memo R) you can see all of the source data that has prompted me to memo about the research process. You can view this as a PDF and look in Quirkos for the original associated memo, or compare it with the memos table in the report. You decide.

You may be thinking that seeing the source quotes for all the research process memos is very helpful, but you want to see the text of the memo alongside the text of the transcript, without having to go back to the memos table, or the Quirkos project. Remember I said, "how you want to see your outputs could affect your decisions of how you decide to work with your memos in Quirkos"? Figure 8 is a case in point. To see a single source's quotes (e.g. Matilda) for all the research process memos, with the text of the memo alongside the text of the transcript, you make your memos in-source (see Fig 1, In-source memo in Matilda's transcript) AND label BOTH the memo and the related source text to a code/quirk (which you will probably call something like Memo. You might have to look carefully, but the memo is there, in the italics that I applied in-source. Of course you can also create a memo in the Quirkos memo column, if you have a reason for needing to double-up in the fashion, such as wanting to see the Memo and source text table in the Report (See Fig.6).

You can also export your memos in Excel/spreadsheet tables, or copy and paste individual ones from the app. Quirkos may not have as many functions and buttons as other software, but aims to enable meaningful and pro-active decisions in your use of your qualitative analysis tools. You will discover (yes, there are more ways to work with memos in Quirkos) and create more, as you work with your data in Quirkos.

References

Barbour, R. (2014). Introducing qualitative research. SAGE Publications, Inc.

Gibbs, G. R. (2007). Analyzing qualitative data. SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Further Reading

Using memos and notes in Analysis https://www.quirkos.com/curated-course/write.html#MemosAndNotes