When codes are themes, and themes are codes: uncertainty in qualitative analysis

What's the difference between a code and a theme? When does a code become a theme? And when was a code really a theme all along? We’ll discuss these questions and take you through real examples of the development of a theme.

What's the difference between a code and a theme? When does a code become a theme? And when was a code really a theme all along? These questions might seem confusing, and even rhetorical, but for many people who are new to qualitative analysis, these issues can quickly become anxieties. In this blog we’ll discuss these questions and take you through real examples of the development of a theme.

What's the difference between a code and a theme?

What's the difference between a code and a theme?

In our YouTube video, we keep it simple, describing coding as a step along the way to analysis. Codes are simple labels that we apply to our data, perhaps describing what we think a small piece of data is about. Analysis is the insight gained from examining coding and data patterns, and asking questions. The tendency in qualitative research is to label anything that is broad-ranging as a theme. Anything small that is discrete or distinct in some way, or perhaps harder to place, would generally be called a code.

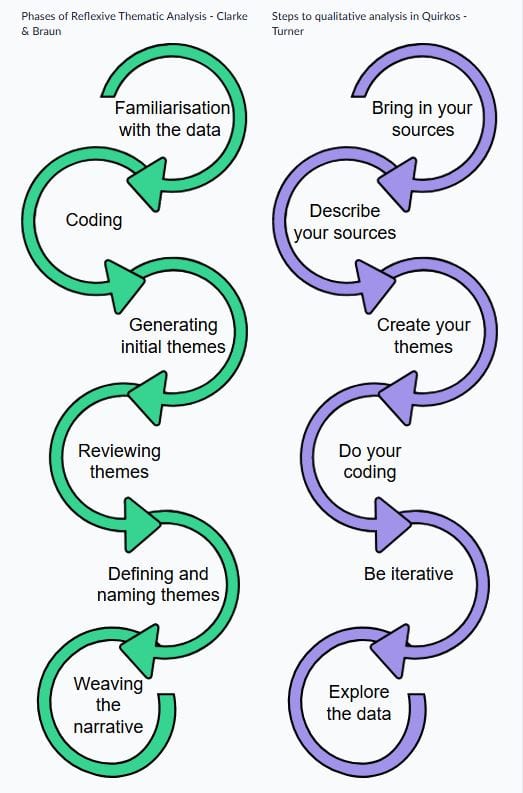

One of the problems with trying to apply a strict step by step approach to qualitative data analysis is that it can give the impression that each step occurs in isolation and is completed before subsequent steps. So we get questions like, "I've finished my coding, now what do I do?" or "Am I allowed to create codes and themes at the same time?" All qualitative research is iterative and contingent, even though processes occur over time, in stages.

Even iterative models are problematic as they do not show concurrent activity. You cannot stop the human brain from subconsciously processing information that it has been exposed to, even if you are consciously working on something else. The model does not really show that how at any given time you might be moving backward and forwards in the process, perhaps describing one part of a transcript in detail, generating broad themes across another part, reflecting on what you learned from different research participants, and thinking about how it relates to what is already known from the literature. You might also be thinking about how any or all of this relates to how you will gather more data. So, it is entirely possible that you might find yourself creating codes and themes at the same time; being rather descriptive in one moment and more deeply analytic the next.

However iterative models do help us understand that we are attempting to move from the merely descriptive, to the analytic and generative. So, the first stages of dealing with your data are indeed often simply descriptive ways to understand and help you keep track of what is in the data. E.g. labeling or coding. These codes or labels often start as simple one or two-word descriptions of what is in the data. They might be inducted from the data itself, as in Grounded Theory, or taken from literature and applied to the data, such from tabulated observations as part of Ethnographic observations.

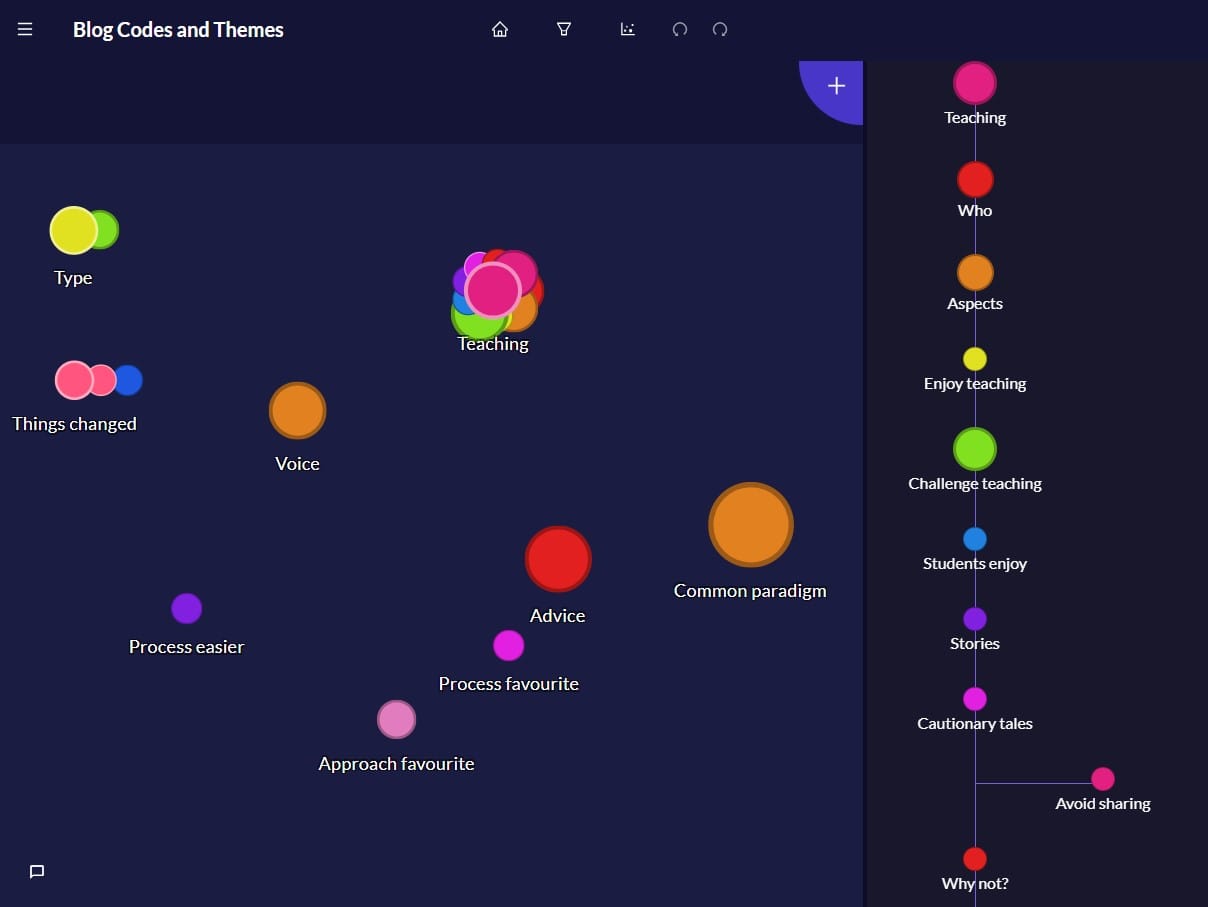

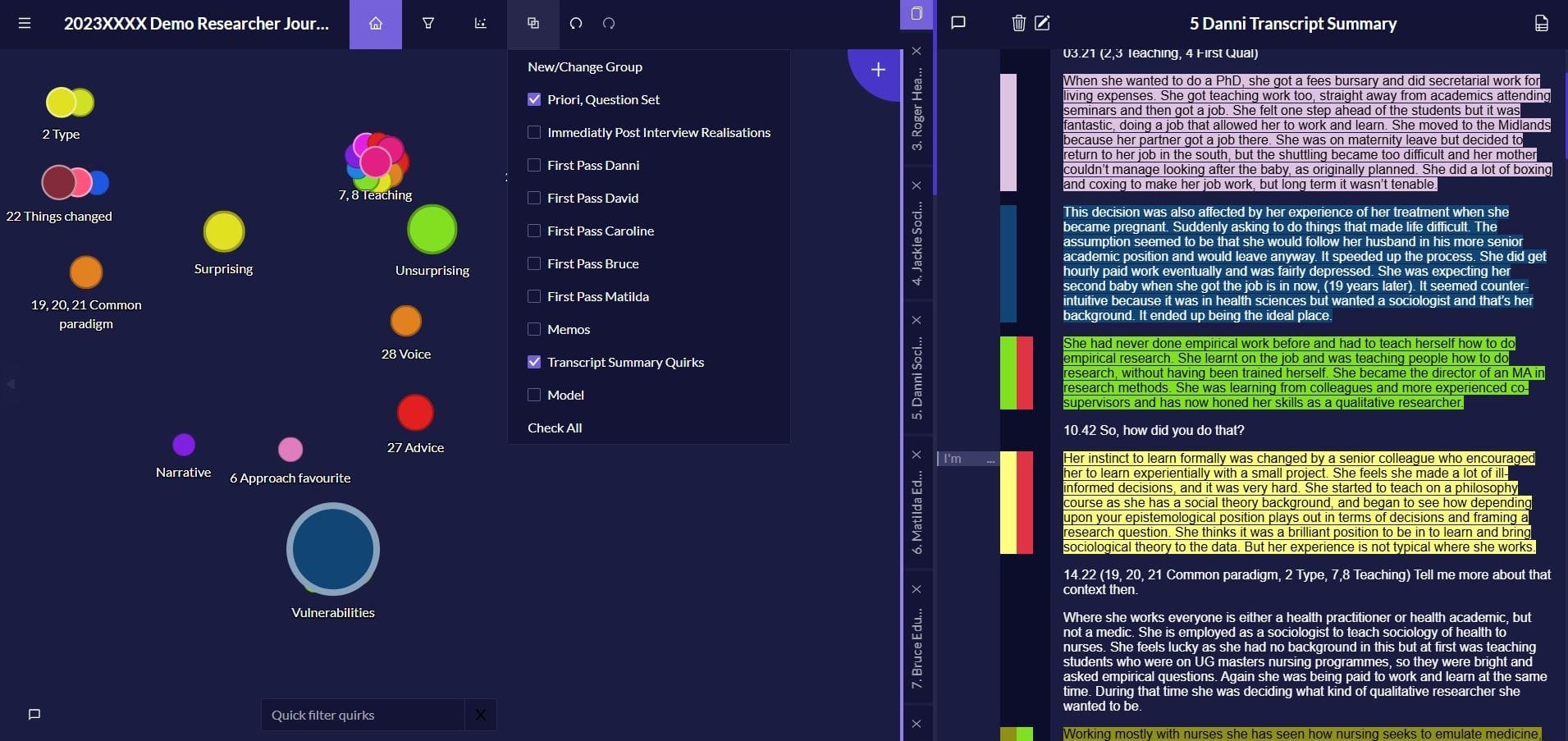

In the Qualitative Researcher Journeys project I had some pre-existing (Priori) codes which were related to the semi-structured interview questions and things that I anticipated that I would look for in the data e.g. Voice). The code Teaching had lots of sub-codes, but Advice had none. Would it end up with any sub-codes? I didn’t know at that point.

Then through examining my field notes (grouped as Post Interview Realisations), close reading of the interviews, examining the detail, and spending time thinking about my data, I generated new codes. In the First Pass of the data (i.e. early analytic reading and interpretation), codes were often isolated and unrelated to other codes. This was just my First Pass; my earliest attempts to make sense of my data.

Another approach to making sense of your data and handling your thinking early on, is to take a wider view. You could liken it to adjusting your lens for viewing your research from fine detail to getting more of an overview. For instance, as Gibbs recommends, you could start by looking at your data as a whole, or in large chunks, by creating interview summaries and transcript summaries. As a result of the tendency to label anything that is broad-ranging as a 'theme', you might describe this activity as creating 'themes'. You might even use a word like ‘category’; ‘categorisation’ is after-all a far more familiar term than ‘thematisation’. However some may dislike it as they think it might be viewed as too rigid, too positivistic, or forcing the data into known patterns (i.e. direct answers to the interview questions), and perhaps a mistaken belief that this is the end point of qualitative analysis.

Read, Compare, Interpret

It is important to note that coding is not a requirement of qualitative analysis. It is merely a way of noting and keeping track of what you notice. I know plenty of career researchers who never call what they do ‘coding’, and who produce analysis through reading, writing and reflecting. You don't have to use computer software either, although it is helpful as a tool for managing your data. Users find Quirkos to be helpful in creative thinking and visualisation of the analysis, but whichever methodological approach you take to analysis, they all recommend reading and spending time with your data. They also make recommendations about how to handle your data so that you can trace your thinking about the patterns you see in your data. Crucially we are all looking for ways to make sense of the patterns and generate new insight about a real-world problem.

When does a code become a theme, and when was it a theme all along?

We get lots of questions about whether to call something a code or a theme. You know that you’ve got some concepts that are unrelated, some that are related, and higher levels of organisation of your thoughts, which most people will call themes. When you are using a labeling approach, whether that is with coloured pens or software, you are creating a system to organise your thinking.

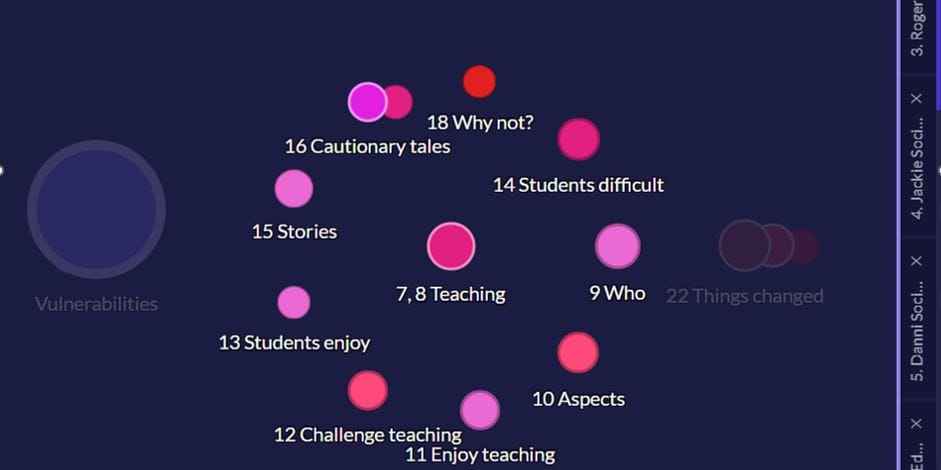

So let's look at a real example from our example open qualitative data set: you can actually see and download the raw and coded data to see how this evolved. Here, it was only through the process of reading, thinking and reflecting that questions of relationships between codes and cross cutting themes were emerging. For example I used the same Priori codes to apply to the Transcript Summaries as the detailed interview transcripts. The Vulnerabilities code emerged from an overview of the data i.e. the Transcript Summaries not the detailed transcripts. Was this therefore a theme? I didn’t know initially if it was broad-ranging and cross-cutting enough for me to call it a theme.

As I examined the data again and again, more evidence for researcher vulnerabilities was found in the data, and I made the decision that it was indeed cross-cutting and I would consider it a theme. It is still labelled as a Quirk/code on the canvas and that is fine. If I was collaborating on the project I would edit the label for clarity.

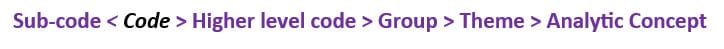

So, my thinking about coding is along the lines of;

Remember, this is just a construct to help me think and remain coherent. It is not ‘true’ or the ‘correct’ way, it is simply ‘a’ way to help me think.

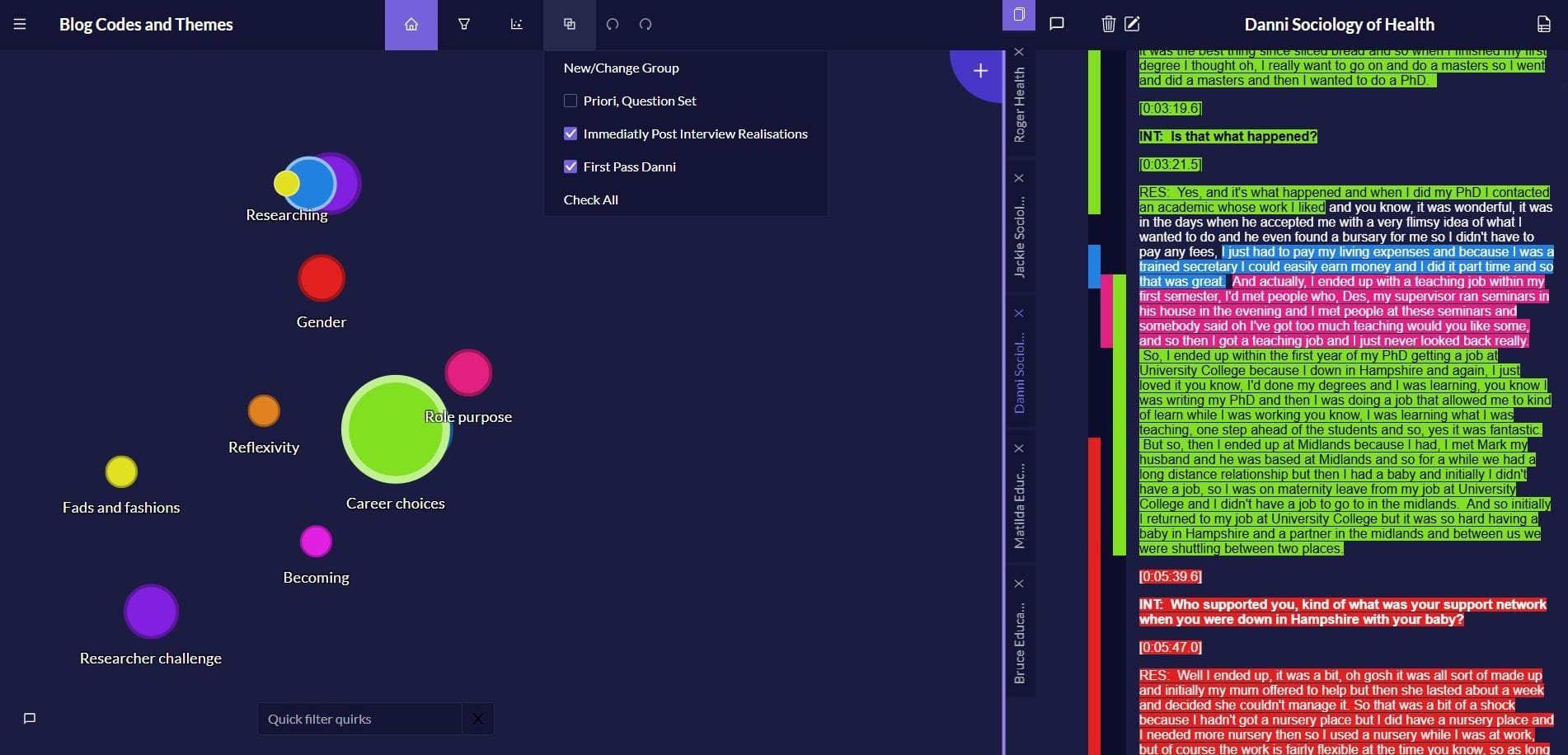

Using Quirkos Groups for labeling Themes

I gave the Vulnerabilities Quirk an additional label as a group in Quirkos so that I could find and isolate the associated data. When we import sources e.g. interview documents, we will label them with attributes or properties that relate to the source. E.g. Age, gender, location, job role, interview transcript, secondary data set, journal article, key-words. We’ll end up being able to query data according to these properties (E.g. What coding have I labelled for all Australian researchers and how is that different to the English researchers who are Women?). So, Properties allows us to put sources into sets. The Groups function in Quirkos allows us to put Quirks in sets.

Look at the two images above and below, I have used the Group function in Quirkos to help me track when and where in the process coding has emerged, such as during the first pass of transcript. Vulnerabilities is an analytic theme, born out of higher order, abstract thinking about the data, so I created a Group for Quirks that I consider to be themes. I didn’t have to do this; I know it’s a theme, but it does help me differentiate quickly. Another way could simply be to change the description of the Quirk and describe it as a ‘Theme’.

Doing it differently

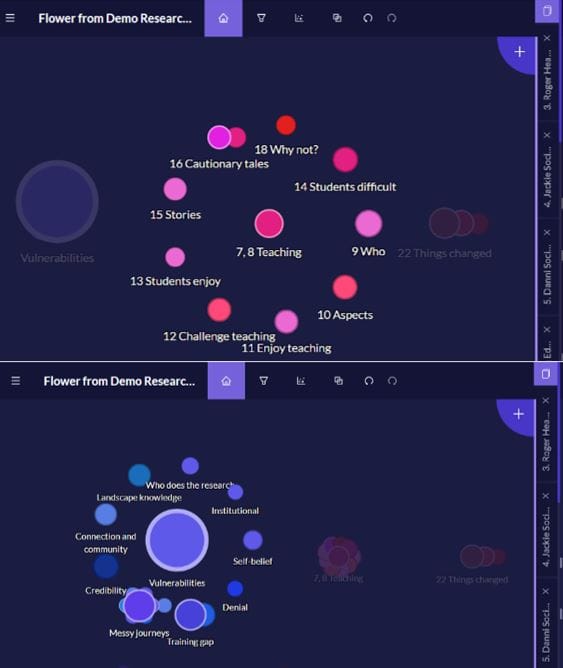

The great thing about Quirkos is that it is methodologically agnostic, so you are not tied to working with your data in a prescribed way. If you can think it, you can probably use Quirkos tools to do it. For example, we tend to think of our collections of Quirks and sub-quirks as bubbles, but one of our course participants, thought of them as flowers. Each flower is a theme. Each flower has its own main colour. It looked very ordered (and beautiful), but they knew there was more thinking to be done. They also weren’t sure how to deal with the messiness that would ensue as deeper thinking would result in the deconstruction of their carefully constructed flowers.

In our experience a lot of novice researchers reach a point of neat organisation and may believe it is the end point, and even experienced researchers can feel hesitant as they delve further and create the messiness that is required for new insights to emerge. In the case of our ‘flower’ researcher we advised saving the project with a new name, like ‘Developing Themes’ or ‘Further Analysis’. This second project could be worked on and developed further, whilst the first iteration was left intact. There is almost never just one iteration of your data analysis; there may be several.

Finally, the differences between codes and themes, and how they are developed will also vary greatly depending on the analytical approach you are taking. Grounded theory, IPA, thematic analysis and others all define codes and themes in slightly different ways, or may use terms like nodes or open and axial coding to differentiate the process. While the advice here is generally applicable to all these approaches, there will be nuances if you are following one of these paradigms closely, so check the fit as you go!

So our answer to those questions, What's the difference between a code and a theme? When does a code become a theme? is that it is not so much what you call it, but what have you have done with the data. The labels are simply constructs to help you manage and order your thinking. You decide the construct.

Further reading

Read more on the iterative and contingent nature of research in our blog on circles and feedback loops https://www.quirkos.com/blog/post/circles-and-feedback-loops-in-qualitative-research

Read our earlier blog on What's the difference between codes and themes in qualitative analysis? https://www.quirkos.com/blog/post/whats-the-difference-between-codes-and-themes-in-qualitative-analysis/

Our free curated online course Doing Qualitative Research has a specific section on analysing and transforming data. https://www.quirkos.com/curated-course/analyse.html

Understand more about moving beyond the First Pass of data analysis. https://www.quirkos.com/curated-course/analyse.html#BeyondTheFirstPass%E2%80%94WaysToThinkAboutAnalysis or consider NOT Coding Qualitative Data, and Delayed Categorisation https://www.quirkos.com/blog/post/not-coding-qualitative-data-and-delayed-categorisation/

Watch How to Analyze Qualitative Data. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=peQBZNWM6w8&t=4s

Watch How to go from Codes to Themes in Qualitative Analysis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1erIajGquxg&t=335s

Read about the Qualitative Researcher Journeys project: Project information: Qualitative Researcher Journeys https://www.quirkos.com/project-info.html.

You can also download the data and associated project files https://www.quirkos.com/workshops/qual/

How to cite this article

Gibbons C.A., (2025). Codes and Themes; names and uncertainty. Quirkos. www.quirkos.com/blog/qualitative-codes-themes-names-uncertainty/