A short guide to getting published

From the outside, getting an academic journal paper published can look pretty straight-forward. Write a ‘good’ paper about your research, submit it to a journal, get some comments back from the referees or reviewers, make some edits, re-submit and wait for the accolades to pour in once it’s been published. Hurrah, you are a published author! Share copies of your paper with all your friends and colleagues! The realities are not so neat.

In this short guide we’ll introduce you to the steps to getting published, and help with some things that you will need to consider along the way. In later posts we’ll discuss these in greater detail, but you can also get a broad overview in this 'podcast' discussion on publishing qualitative research:

Write a ‘good’ paper

If you want to be published you need to write a ‘good’ paper. But what constitutes ‘good’?

As a starter, ‘Good’ tends to mean a piece of writing that has something novel, new or insightful to say, where appropriate research and analytical techniques have been used. It also needs to be well written in your target language, neatly formatted, and appropriately referenced. ‘Good’ is not a dense, unstructured narrative, that attempts to describe the entire process of your research or has little to add to, or challenge, what is known or understood about the world.

Research papers, articles and chapters are short (well, compared to a thesis). So you should focus on an aspect of your research that brings value to our disciplinary understanding. In qualitative research there is such an emphasis on this that little attention is given in papers on how the research is undertaken (hence the ‘Black Box’ label on our behind-the-scenes resources).

Academic writing generally uses highly specialist language. Those new to research can be tempted to use as much specialist language as possible in order to impress others. This can too often tip over into using language that is so obscure or poorly understood by the author it renders sentences meaningless. Take care to adopt a writing style that is appropriate for your audience.

At this point you may be thinking that you still have lots of questions about what constitutes ‘good’, and even more importantly, how can you find out? Many of your questions around style, structure, and which content to focus on will be answered, or directed by, where you choose to submit your paper. Academic journals publish guidance to authors on their web-sites, which address matters of style and structure (e.g. Qualitative Inquiry). They also have statements on the scope of the journal, which should guide you in what to include in your paper, and what to leave out.

Choose the ‘right’ journal to publish in

Potentially this is one of the most difficult decisions to make. Publishing in well-established ‘top’ journals is clearly a goal for many who wish to pursue an academic career. It seems common to simply approach journals suggested by mentors and advisors, or journals with articles you have cited in your paper, or read during your research: these are perfectly reasonable approaches to take. But you should consider who you want to communicate with and who the journal is aimed at, rather than simply following others, or looking at measures and indices.

Ask your library services staff. At worst they’ll be able to help you understand your library’s catalogue system so you can use it to get ideas of which journals you might approach. Librarians are usually data scientists with copious knowledge and expertise in all matters of publishing, and are employed to facilitate staff and students in the appropriate use of, and access to, publications.

When I was doing my PhD, (was it really twenty years ago?!) I was told to avoid online publishing. Academics can be a cautious bunch, and online journals were an unproven concept. Similarly, there is caution around new journals as they are unproven. But if you are truly cutting edge or interdisciplinary in your approach it can be very difficult to find appropriate established journals that have the scope to include your research. In the absence of indices and a journal track record, you need to consider the reputation of such things as the editors, the editorial board, and authors in the early editions. On the bright-side, there may be less competition to publish in these journals. No one can tell if it will disappear after a few editions or be the world leader of an evolving discipline in five years’ time.

There are journal ‘matching’ services and sites available, that use your key words or abstracts to identify where papers with similar themes are published. But now it’s my turn to urge caution about untested services. For now, I’ll point you to Web of Science, to help you find out more about the scope of journals (your institution provides you with login details). Look out for a future post to help you understand more about matching services and journal rankings.

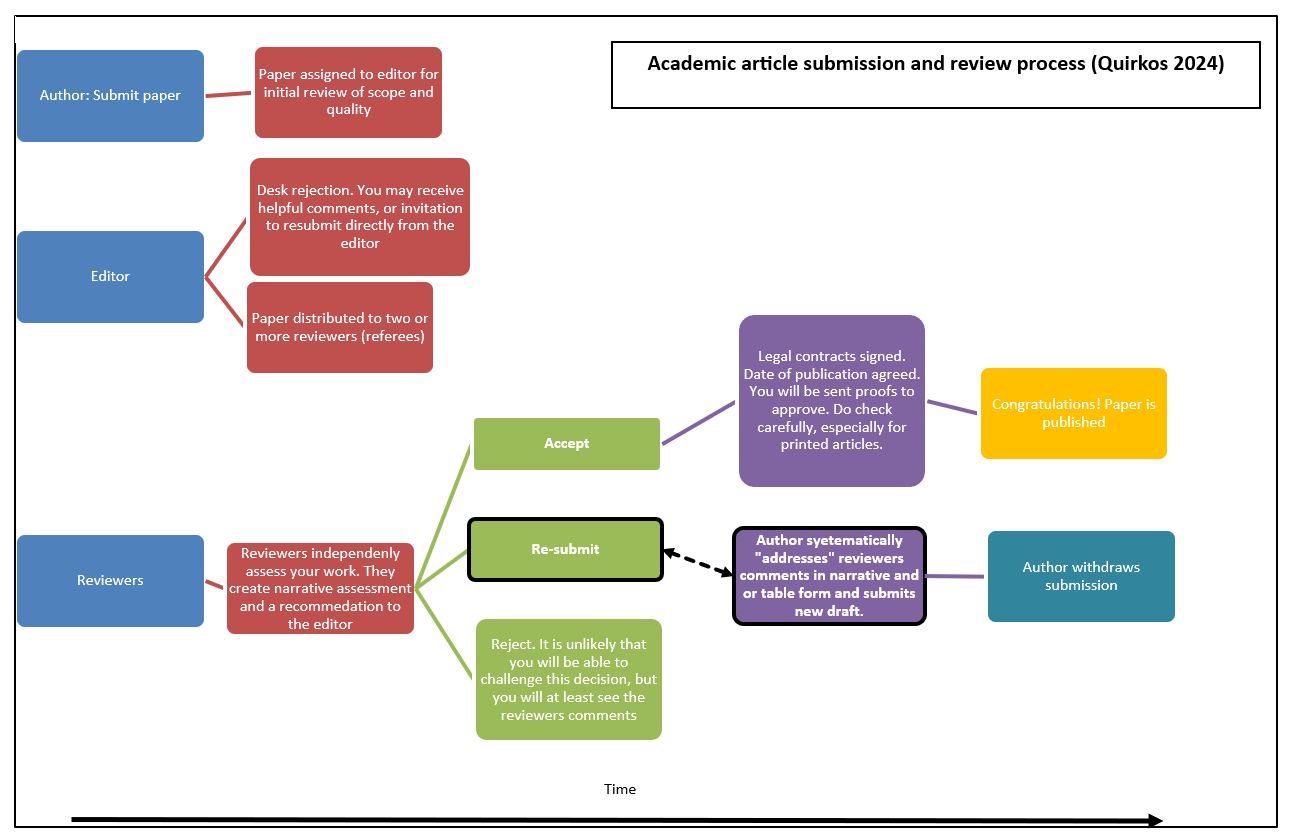

Understand the journal submission and peer review process

Journal websites will detail how to submit your paper, and in what form. Some are extremely specific and you should carefully follow their requirements or you risk instant rejection. The review process is almost always anonymous in some form. Single-blind review means the reviewers know who you are, but you don’t know who they are. Double-blind is seen as less open to abuse as only the editor knows who’s who. More models are being explored by journals to ensure fairness, such as triple-blind review or even a return to open review, where all parties know who is saying what.

Your reviewers (sometimes called referees) will assess your work and give detailed comments, which will be returned to you via the editor. It is unlikely that your paper will be accepted straight away. It may even be rejected. Usually you will be asked to address the reviewers’ comments and resubmit. This may go through a couple of rounds before acceptance, and in some cases may still result in rejection. Whilst we do not recommend slavishly following reviewers’ comments and recommendations, you should give them serious consideration. Your response should demonstrate explicitly where, why and how you have changed your paper (or not) to address reviewers' comments or concerns. This can be a time-consuming process, but it is a normal part of peer review. In the Qualitative Researchers Project data, Danni talks about her and her co-author’s response to reviewers’ detailed critique. They spent a great deal of time redeveloping their paper with innovative insights, and ultimately their resubmission was successful. Disputes do sometimes occur, but your point of reference for queries and resolution is the editor or the editorial board. Sometimes you may have to accept that this is not the journal for you and submit elsewhere.

It is important to note that you should not submit your paper to several journals at once and hope that one of them will accept it. This is very unprofessional, and you can expect your paper to be rejected instantly if the editor finds out. If you, for any reason, produce two similar papers and submit to two different journals, perhaps one aimed at academics, another at practitioners, then you should declare this to both editors. There are other practices that you need to consider if you are to remain professional, or for others not to take advantage of you and your hard work.

Authorship, ownership, and publication ethics

In some disciplines and academic cultures it was normal to gift or grant authorship to a supervisor or someone who had helped with the research in some way, or who was simply powerful enough to demand that their name be included. Journals now usually have policies that actively frown upon this kind of ‘gifted’ authorship by defining exactly who may be named as an author. They also offer alternative ways to acknowledge other people’s contributions, (e.g. those who've given advice, and help with transcription or analysis techniques). The Lancet was one of the first powerful medical journals to do this and other journals quickly followed, including the British Psychological Society https://www.bps.org.uk/guideline/statement-policy-authorship-and-publication-credit.

Whilst I think my advisers were being over-cautious about avoiding online journals, I think their caution around payments in publishing was justified. But a ‘never pay anyone’ approach masks a complex picture of how academic publishing is funded, and when it is normal to charge an article processing fee (APC). Not all journals who charge a fee are considered predatory, but predatory journals are on the rise. They will usually approach you to offer to publish your work relatively quickly, for a 'small' fee - a few hundred dollars. Even worse, some of them have titles that are deliberately similar to higher ranked genuinely respected journals. These are not 'new' journals trying to establish a new academic view; they are trying to rip you off. As a minimum to protect yourself:

· Be wary of similar sounding titles, such as, Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, and Psychology and Psychotherapy: Research and Practice. The first is a reputable journal from the British Psychological Society, the second is one that I have just made up. (I've taken care to check that it doesn't actually exist, so I'm not trashing the reputation of an unsuspecting journal).

· Check the institutional webpages of claimed editors. Do they list their role as an editor of that journal? Email them and ask. They'll be glad you did if someone is using their name without their knowledge.

· Cross-check any claimed impact factor or index score. Overstating their scores is a clear indicator to stay away from that 'journal'. (We'll show you how in an upcoming blog).

If you are a student or staff at an academic or research institution then your institution will have specialist guidance for you. Your Library and/or Information Services will not just have policies and guidance, but information specialists and managers, who are experts in this area. You might fear that getting involved in institutional bureaucracy will slow you down, but it will help you ensure that you are being treated 'fairly' (under current norms) and that you have ticked all the relevant boxes in terms of being registered with relevant author identification, and open publishing. I urge you to speak to your librarians.

Then there is the question of who owns the rights to distribute the paper. Journals might like to think only they can distribute the paper, but many institutions have pre-print archives, and in practice many academics will send copies to whoever asks for them.

And, we've all come across the paper that we are desperate to read, but can't access without paying. This is could be because you do not belong to a large institution with library access rights, or that your institution has not subscribed to that journal, or the originating author/institution has not paid for the paper to be open access. We’ll definitely be bringing you more on ethics in publication, Open Access, and how to choose suitable journals, and avoid unsuitable ones. Until then you can explore more about the other unspoken aspects of research in our blog: What’s in the Black-Box of the Quirkos Qualitative Researcher Journeys Project?

Quirkos is simple qualitative analysis software, designed to immerse you in your qualitative text data and help you to understand it quickly and easily. It can be used for any kind of textual data, including literature review and drafting your own writing ideas or publications. Try it for free.