How to actually start your qualitative analysis

Some practical solutions you can use to help break through the initial overwhelm of having a lot of qualitative data to analyse, and get close to your data in record time.

This post is Part Two of a two-parter about why and how you should get to your qualitative analysis as soon as you can.

The first post covers why you should start your qualitative analysis earlier than you think, while this one talks about some practical solutions you can use to help break through the initial overwhelm of having a lot of data to analyse, and get close to your data in record time.

Put all your information in one place.

It can be harder to start your analysis when you don't have a unified system for organising your data from start to finish. You might have a complicated system of multiple apps and programs, requiring a lot of mental load just to remember where you put something and what steps you need to take to process and manage the data you have. You might have to get all your participant data into a spreadsheet, make a separate to-do list, and then act on those to-dos in your chosen qualitative analysis platform (whether this is a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software like Quirkos, Microsoft Word/Excel or just pen and paper!). All these steps add up and create barriers for you to begin your analysis early. They create arbitrary barriers between you and your data, because, well, you haven't cleaned up and transferred all this data in the right program, so what's the use in starting?

I'd estimate that in 95% of cases, if the data has been collected and you can read it, you can start working with it. A practical way you can make things easier on yourself is to purposely design your system to smooth out the process between gathering and analysing data. Wherever possible, use just one program/system for all your research and analysis, at least up until you are writing up. Rather than transferring a spreadsheet to a to-do list to your chosen qualitative analysis platform, try to keep everything about the research project on one platform for as long as possible.

Most qualitative data analysis software has the option to categorise your sources and transcripts with custom metadata, but you can also use this metadata in an empty source to track the stage of data gathering you're at (e.g. has this participant handed in their consent forms? have you scheduled an interview yet?). Keeping everything in one place is a great motivator for early analysis, because you break down what would ordinarily be a laborious task into one that's much smaller and easier to handle from source to source.

Find out more about how Quirkos can help manage your data sources in our previous blog post!

Keep your plan flexible.

I thought of myself as a pretty organised student. I had a study journal, calendars and timelines for all my assignments. But while you can make all the plans in the world, research will inevitably be messier than you anticipated. Likewise, no two projects will require the same steps carried out in exactly the same way, so a more tailored and flexible approach will suit your research endeavours better.

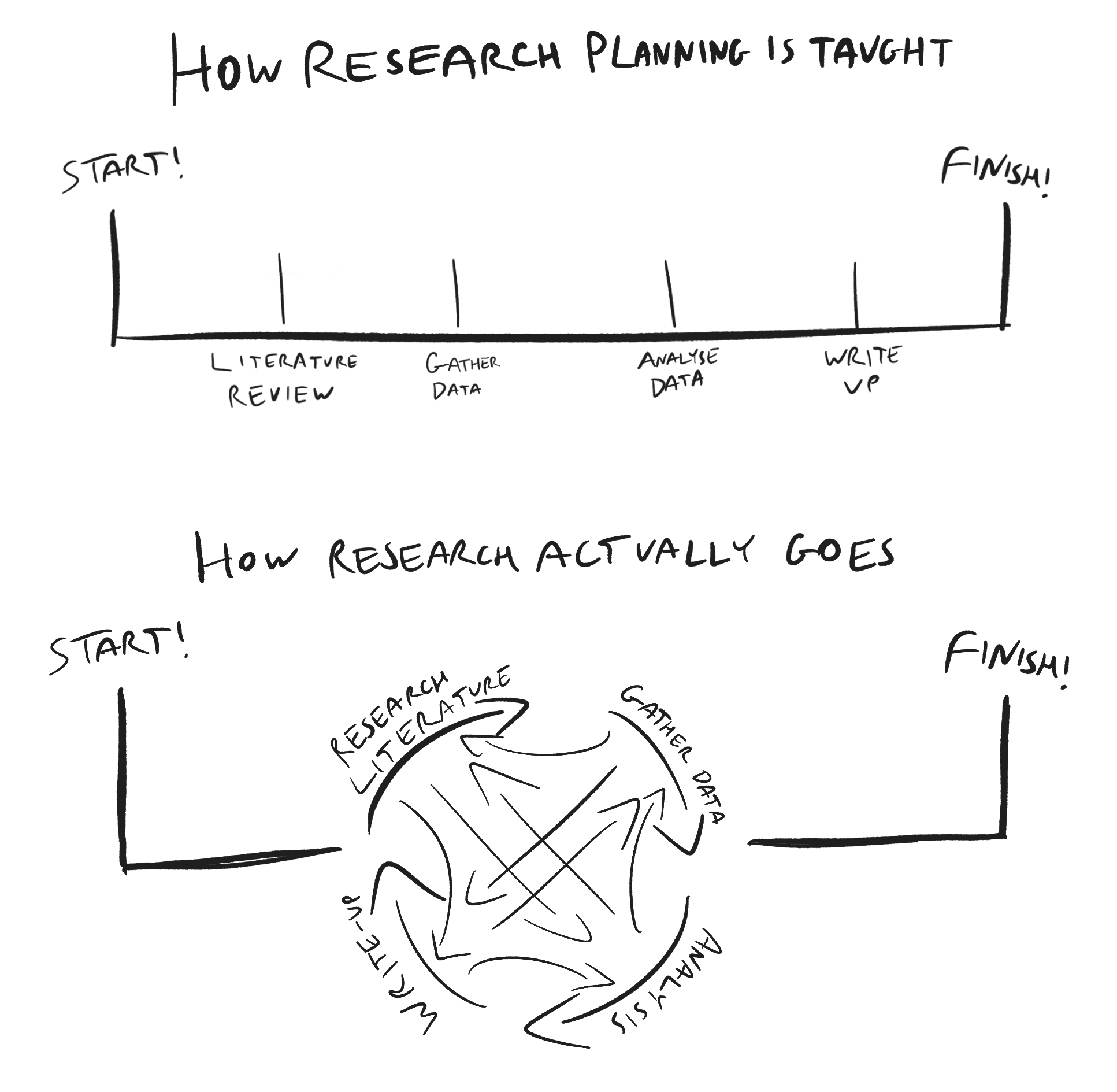

The way that research is taught at university, especially to undergraduates, is often too linear and rigid, which can create more anxiety when the research process is messier or more uncertain. The process gets oversimplified into stages of preliminary research, but these stages tend to overlap and work in a cycle instead.

It doesn't matter what system (or lack thereof!) you use. What matters is your mindset around common time management concepts, like setting tasks and self-imposed deadlines.

Firstly, I would highly recommend that you only set deadlines that are output based – that is, the step is 100% necessary for your end goal. If you're delivering a written assignment, your deadlines should be for the amount of words you've written or the state of your draft. So three weeks before your deadline you might want to be at 2500 words, at two weeks you might want a completed rough draft, and at one week you might want a draft you'd be happy to submit, even if it's still a little rough around the edges. Two days before your real deadline, maybe you'd like to have all your formatting and referencing checked and done. (Bonus: take all your deadlines and push them a week before you think you need them done. You'll thank yourself later.)

It's not a good idea to make arbitrary deadlines for tasks that may be ongoing till the very end of the project. These tasks include gathering data, analysis, and reviewing the existing literature. Make peace with the fact these tasks can take wildly different amounts of time depending on the project, that they are never really 'done', and that they may have to be revisited during the writing-up process. You're not going backwards if you have to go back to your primary text after you've already started drafting – you're going forwards, because you noticed a gap in your analysis and you're taking action to fill it!

It’s important to remember - especially if you are working on a university assignment - that you are using analysis to prepare a research output, not just researching for the sake of researching. Just as analysis can stretch on longer than you expected, you might also find the opposite – that you anticipated needing to analyse fifty interview transcripts only to find you reached data saturation by the first ten.

To account for these normal shifts in priorities, organise your tasks day-to-day instead. Ideally keep the tasks small enough that they're achievable within a day or less.

If you struggle with picking tasks to prioritise, look at each item on your to-do list and ask: what would I regret not doing the most? (Or, in line with one of our previous posts, what will my future-self thank me for the most?)

And if you're not sure what your tasks should be, try my next tip:

Keep a reflective journal.

To help stay focused, write all your thoughts, feelings and tasks in a research journal. If you're abiding by the principle of reducing the number of documents you have to open, you could create a blank source in your qualitative data analysis software and put all your thoughts in there, or otherwise use a program like OneNote, Notion, or Word. Date your entries to see how your project evolves over time.

Keep your journal open as you are researching and analysing, so you can use it to consider how your ideas are evolving into an argument and, also, what seems to be missing in your current work. This will help you to retain focus, find out the areas and topics you’re drawn to the most (and which may be the best for your research output), and also log any thoughts that may not immediately fit into your argument, but may be useful for later. That way, it won't feel so much like you're pigeonholed into one topic as you're analysing – if you're continually seeing the same theme come up in your journal but not in your analytical notes, it gives you a chance to rethink what you're focusing on.

We’ve already written about the power of reflective journaling for qualitative methodologies, and how Quirkos can help you keep a journal right in the same project file as your analysis.

Start with a passage that feels easy.

Maybe it’s a passage that jumped out at you when you were doing your initial reading, or when you were collecting your data in the first place. It could also just be practically easy, a short but evocative piece of data. Use it to test your ideas and any themes you've already decided you'd like to code for.

Remember also that ‘easy’ is subjective. You might bristle against starting with the easiest passage, because a lot of university mark schemes ask you to make an ‘original claim’, and you might assume that analysing something that feels easy will mean your argument and claims are ‘easy’ to make as well. But everyone has different analytical interests. What interests you or feels easy to analyse might not be so easy for everyone. And, remember, you’re not tied to actually including this 'easy' passage in your research output. This is just to oil the wheels, to get you started on something and give you the positive motivation of completing it to help you get started – if you need to – on tougher passages.

Use anchors for your research focus.

Your journal can be one anchor, helping you to prioritise and keep notes on your process. You might also like to consider keeping a more formalised codebook if there might be a while between your analysis and write-up – as this will help you to clarify your focus and interest.

You could also use visual cues, such as writing your research question/s on a sticky note and putting it on your desk, computer or laptop monitor, so it’s right in front of you while you’re doing the analysis. A cue like this can help you continually ask yourself, ‘Does this really fit what I was looking for?’, while you're deep in the data.

Ultimately, self-reflection, flexibility and self-confidence is your best route to making a start on your research project before it’s too late. Try out some of these tips and let us know in the comments, or on our Twitter, if they were helpful for you.

Be sure to check out Quirkos, our software which is designed to keep you close to your qualitative data while undergoing analysis and writing up! Make use of memos to reflect on your experiences, use our chat function as your own private journal, and use categories and subcategories to highlight areas of interest in qualitative texts to help you narrow down your focus.