Beyond methodology: What is post qualitative inquiry?

Qualitative research often follows a linear process, particularly if you only look at the output at the end. Most qualitative papers follow the same structure of 'introduction, method, results, conclusion'. But the research process is often messier and less linear than this would imply (we provide an example of this here). Research methodologies try to bring order to the research process, providing a step-by-step procedure to follow. This can help to produce valid and reliable data, and avoid ethical problems. But what goes missing or unsaid in this process? Are the goals of methodology futile?

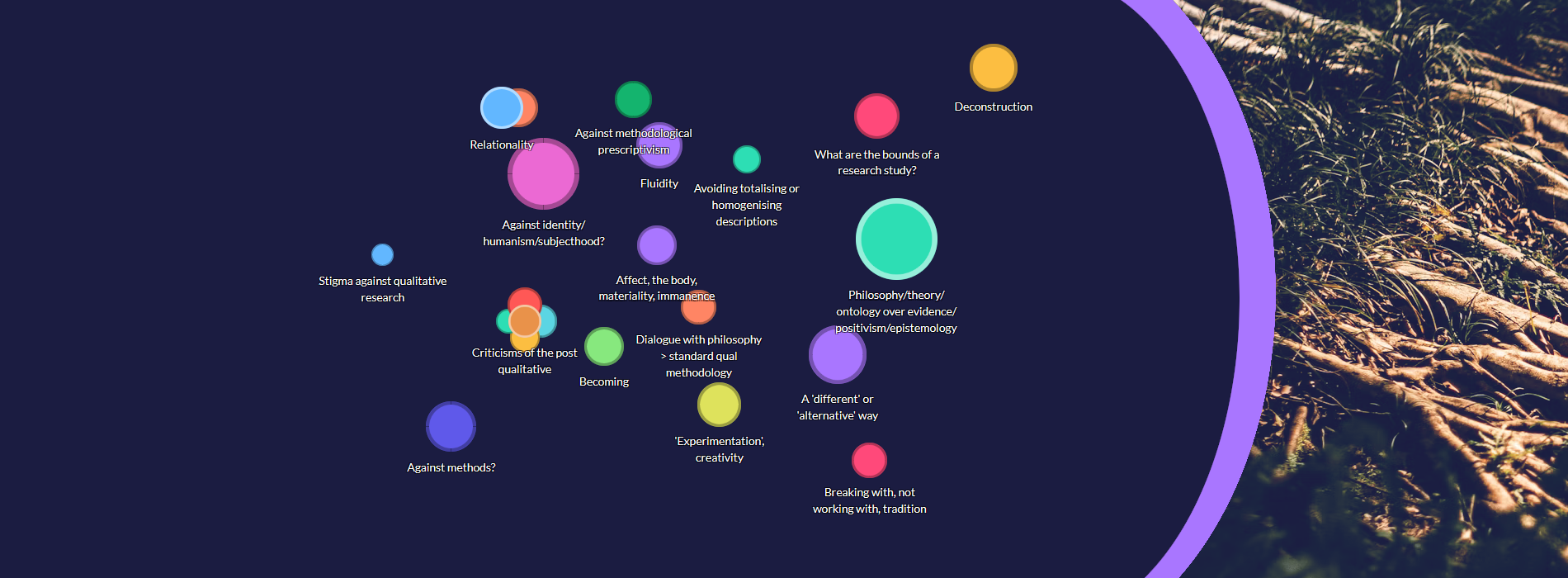

This blog post tries to summarise the main ideas of post qualitative inquiry, one possible 'answer' to these questions, but also acknowledges the futility of this aim. Post qualitative inquiry asks us to make peace with indeterminacy and uncertainty – or, at least, try not to ignore them. Asking 'what is post qualitative inquiry?' invites a stable definition of the term, which risks closing off its complexities and possibilities. Equally, I think the approach could do with having some 'ways in' that are a bit more familiar – not to the degree of producing a prescriptive "handbook", but because the theory often is opaque in its radical opposition to standard qualitative methodologies (Kuecker, 2020). It is difficult to conceptualise post qualitative inquiry at first except by explaining how it diverges from standard qualitative methodologies, so we will begin there.

Perhaps you are interested in applying philosophy to your qualitative research. In many conventional qualitative methodologies, you may be expected to bring your own philosophy to your analysis, but leave the methods alone. But not all philosophies are compatible with the methods. Many methods 'close off' the concepts of data and analysis, considering them to be self-explanatory. But poststructuralism creates sticking points for this assumption. A core idea of poststructuralism is that definitions are incomplete, and boundaries are unstable. Hence, there is no stable definition of 'data', or 'a research field', or 'validity'. A poststructuralist analysis of methodology might ask: is qualitative methodology and qualitative coding arbitrary? Can research be more than just making 'sense' out of existing phenomena, which may be impossible to rationalise (though, of course, we try anyway)?

Posthumanism troubles some of the assumptions of qualitative methodologies as well. A lot of qualitative methods focus on human experience, and elevate the human voice as an authoritative source. But to posthumanism, this is an anthropocentric perspective. Posthumanism suggests that the human subject is entangled with their environment and with nonhumans. To exclude this from consideration results in the 'human' being seen as the only agent capable of affecting the world, while the world is reduced to a 'thing' that humans experience.

After Elizabeth St. Pierre noticed the incongruences between poststructuralism, posthumanism and qualitative methods, she coined 'post qualitative inquiry' to describe a poststructuralist alternative to qualitative methods (St. Pierre, 2023). When she coined the term in the early 2000s, US social sciences were becoming increasingly positivised and directed towards profit, with rigid ideas about what counts as 'valid' research (St. Pierre, 2021a; Gildersleeve, 2018). But the post qualitative inquirer does away with all conventional qualitative methods like interviewing participants and coding data (St. Pierre, 2023). Instead, post qualitative inquiry is about reading and writing in dialogue with philosophy, in order to develop new ontologies (new ways to approach and explore the 'nature' of experience, being and becoming).

What counts as 'post qualitative inquiry' is debated. As Murris (2021) suggests, the world is "always on the move" and always becoming – and so is post qualitative inquiry. Defining post qualitative inquiry too rigidly may undermine its project to acknowledge the fluid definitions and shaky boundaries of existence. As a form of 'research without boundaries', post qualitative inquiry appears to be a big tent for 'underdog' qualitative research practices – in particular, creative practices which eschew standard research procedures and experiment with process. But I would side with Kuecker (2020), who suggests that:

Post qualitative inquiry is not a genre with very thick boundaries, but it has a few elements that help it remain something at all—and those elements are that it remains a philosophical mode of inquiry, engaged in relentless readings of theory that generate inquiry. (Kuecker, 2020)

Post qualitative inquiry argues that conventional methodology can only go so far in producing genuinely new or surprising insights (Koro, 2020). As a post qualitative inquirer, you may not immediately know the subject of your research, or how it might evolve over time. Your goal is to read philosophical theory and think for long periods of time about this theory, trusting that your own ideas will flower (St. Pierre, 2021b). With post qualitative inquiry, there is no precise methodology or steps to follow, and there is no "data" to analyse or epistemology of knowledge (there is in fact no way of knowing or creating knowledge for certain). But there is ontology, and there are philosophical ideas, in a tangled web of conversation with each other. Your work as a post qualitative researcher is to become embedded in philosophy through the "labour of reading" (Kuecker, 2020). By doing so, it becomes possible to produce new ideas about perceiving and experiencing the world.

The goalposts of standard qualitative inquiry have therefore been moved: the goal is not necessarily validity, but newness, unique ideas. However, this comes with its own problems. Something being 'new' does not necessarily mean that it is a helpful contribution to knowledge. Gerrard et al. (2017) cautions against establishing a new binary between 'old qualitative methods' and 'new post qualitative inquiry'. This would suggest that there is no value to be found in past practices or research methodologies, and that post qualitative inquiry is definitively more 'advanced' than standard qualitative methods:

Post-qualitative inquiry is now able to state itself as more progressed and progressive than earlier or other ways of knowing. Indeed, the post-qualitative rendering of humanism—as solely concerned with evoking a stable categorical subject—eclipses a much messier, diverse, and contested intellectual genealogy of humanism. Here, humanism and feminist qualitative research are positioned as the problematic past, while the myriad “posts” and “news” are heralded as arenas for possibility. (Gerrard et al., 2017)

This also ignores that post qualitative inquiry is not exactly 'new'. Post qualitative inquiry is influenced by poststructural philosophers and texts running as far back as the 1960s (Wolgemuth, 2022; Lester, 2020). So while post qualitative inquiry strives for newness and uniqueness, it is important to avoid overstating its newness, and acknowledge the prior texts and innovations (including within more conventional qualitative methodology) that made it possible (Lester, 2020).

This post is an attempt to straddle the balance between offering a taste of post qualitative inquiry, and a list of ingredients. It is not a recipe to follow, but a stocked kitchen for you to play around yourself. Rather than this post being the only text that you read about post qualitative inquiry, I hope it leaves you curious and interested in experimenting with post qualitative approaches, because I think that aim is more aligned with the subject of this post.

If this post inspires you to perform post qualitative inquiry, remember that there are no shortcuts on philosophical and theoretical understanding. It is your job to do the reading, and the reading is in some cases notoriously difficult. If you can accept that you won't understand everything and that's okay (especially not on a first reading), poststructural philosophy can often be quite enjoyable to read – and the more you read, the easier it will get, as you begin to make connections between different philosophers and concepts.

Post qualitative approaches deprioritise the subject.

Many qualitative methodologies are humanist, being organised around the assumed existence of a "human subject", with a stable identity. Humanist data collection tends to prioritise the speech of the human subject as an authoritative source of data. Identity-based approaches may suggest that the subject's identity impacts their experiences, without acknowledging that identity is performative and fluid. Humanist and identity-based approaches centre humans as individual actors and agents with free will, who solely act upon broader social forces and environmental factors (rather than those 'external' factors acting upon and defining them).

By contrast, many poststructuralist philosophers disagree that the speech of human individuals is worthy of study (St. Pierre, 2023). Voice and standpoint (which we discussed in this post) are generally not considered useful for post qualitative inquiry. Studying only the speech of individuals does not produce new insights about how subjects and identities are constructed but instead reinforces the construction of existing human identities, making them seem more 'coherent' and 'real' (Rautio, 2021). Post qualitative inquiry suggests that identity is relational. People's identities are defined by their environment and by others around them, as well as by what they are not as much as what they are. Identities are also indeterminate/fluid, in that they can change over time, and shift depending on the moment, social context, and behaviour. After you have acknowledged that identity is constantly in flux, it is harder to justify studying one specific identity. Post qualitative researchers may not work with participants, or if they do, the bounds of who can be a participant may be blurrier. The focus may instead be on how people interface with the world, the discrepancies between one's sense of self-identity and the actual contingency of identity and subjecthood, and the points at which people and their environment become intertwined.

This comes with its own problems, of course. By deprioritising the speaking subject, post qualitative work risks reprioritising the researcher's perspective, as the researcher claims special authority to speak 'beyond' identity (Aagaard, 2022; Gerrard et al., 2017). Researchers may therefore produce an insular and solipsistic work in their attempts to erase themselves from the research (Kuecker, 2020). Beyond the bounds of post qualitative theorising, it is hard to say what this does for deconstructing identity. Identity and subjecthood is still reinscribed through voice, but the voice is now solely coming from the researcher.

Post qualitative inquiry may also risk forgetting that a person has to be involved in the authorship of theory (and that a person's works may, in turn, author their identity). Aagaard (2022) summarises this issue nicely:

Even if Derrida taught us that language cannot transport meaning directly from one person to another, we evidently have learned this lesson from Derrida, so perhaps we can also learn valuable things from our research participants, too? (Aagaard, 2022)

The author may be dead, but the canon of texts and authors selected by the post qualitative researcher is very much alive. Post qualitative researchers may value a select few philosophers for elucidating being and truth. Discarding identity, rather than deconstructing it, means there is no way to interrogate why they may have valued those particular philosophers over others, or why they considered their selection a 'neutral' decision. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a lot of post qualitative research draws from white Western writers, and there may be little consideration over how this subject position might impact their perception and philosophy. That being said, some post qualitative researchers are now challenging this through their incorporations of postcolonial theorists [Wolgemuth et al, 2022; Bhattacharya, 2020].

Post qualitative approaches break with conventional methodology, and don't subordinate theory to methodology.

For post qualitative inquirers, conventional qualitative methods are too focused on describing and interpreting preexisting data, and attempting to make 'sense' of it – as we've discussed, this may be a futile task. Post qualitative inquiry takes aim at methodological prescriptivism: the idea that there is a 'right' way to do research, step by step. Methodology leaves little room for theory, or only permits it as an accompaniment to the method. They also impose rigid ideas of "data", "field", "researcher" and "participant" (St. Pierre, 2023).

Yet doing away with methodology as a whole may not be the right move. Methodology is not just there to circumscribe the bounds of 'valid' research or assume one view of reality. It is also a way to encourage greater accountability in how knowledge claims are made and constructed, so that research is more transparent and open for critique. Gerrard et al. (2017) argues that qualitative methodological standards made it easier to highlight social biases in research institutions, allowing liberation-based methodologies to develop (e.g. feminist, postcolonial, anti-racist and/or queer methodologies, to name just a few).

But if it's not possible to take the middle of the road between methodology and poststructuralism (at least, according to St. Pierre [2020]), what is the answer? I would suggest it's to be more reflexive and honest about the limitations of research, and of writing as a form of communicating that research. In the case of research, it's good to be aware of what your approach excludes or stands against, and to be mindful that you are not placing your work in an oppositional binary. After all, placing your research approach as one end of a binary structure is not very poststructuralist. As for writing, it's good to be aware that language is an imperfect method of communication and can only represent (without perfectly recreating) what it discusses, so your readers will unavoidably bring their own meanings to your paper (Kuecker, 2020).

Post qualitative approaches try to reflect the full complexity and interrelatedness of the world.

Post qualitative approaches are less concerned with "what is" than what is becoming, how elements interact with one another and define one another. Deleuze and Guattari (1987, cited in Murris, 2021), call this tendency 'rhizomatic', like how plant roots can branch off and intermingle in complex iterations. The world is relational and complex, evading the easy analysis or compartmentalisation of just one subject at a time. Post qualitative inquiry sees conventional qualitative analysis and coding as a holdover from the Enlightenment, attempting to box off and categorise phenomena (St. Pierre, 2018). This sort of analysis is ill fitting for the more ambitious and nuanced aims of exploring ontology – being in the world.

But how can we approach the task of analysing the entirety of existence? Post qualitative inquiry can risk becoming broad to the point of becoming unintelligible, not saying anything specific at all (Aagaard, 2022). But I would argue that it is still the researcher's role to intervene and identify connections that are of interest. Any act of writing excludes more than it represents, so any form of analysis through writing will always be incomplete – so, some pruning is appropriate. The key is to not close off potential avenues of comparison before they have opened, and be aware of what you may have automatically dismissed as 'irrelevant' or a 'mental leap'. The connection may be closer than you think.

Regardless of whether you are doing post qualitative inquiry, it also helps to reflect on what you want your research to do. Poststructuralism opens up promising ways of reconceptualising 'reality', acknowledging that our understanding of the world is always in flux, allowing many concepts that seem 'self-explanatory' or 'just natural' to be called into question. But our acknowledgment of uncertainty should not prevent action, particularly if our research aims to produce positive political change (Wolgemuth et al., 2022). While your subject matter may be intimidatingly all-encompassing and entangled in interrelated webs, the research should still have an aim in mind, even if it's not as specific or as targeted as it would be in other disciplines.

Post qualitative approaches are often material.

Post qualitative works often explore posthumanism, bodily experience and materiality, including 'affects' – which, to summarise (quite incompletely), are feelings which have a physicality to them, beyond the capabilities of language to describe. These fall roughly under 'new materialism', which is a collection of philosophies that feel that the philosophies of discourse and representation are not sufficient for studying the world (Truman, 2019). Rather than reducing existence to language, representation and discourse, new materialism asks that we continue to pay attention to how material, physical factors affect behaviour, experience, and being. New materialism also studies the life within that which is often objectified and Othered in conventional research (such as the body, the environment, 'data'), and acknowledges the agency of "non-human actors", decentring the human (Aagaard, 2022).

Much like with the difficulties with rhizomatic analysis, the focus on materiality and affect can sometimes lead every possible affect or sensory experience to be included in a paper. Wolgemuth et al. (2022) suggest that it would be helpful for post qualitative researchers to intervene more, to decide which specific materialities are important, as opposed to simply describing all sensory experiences observed within the research project.

In this post, I've advocated for transparency and reflexivity, even when you are undoing methods and deconstructing data. You may be interested in my follow-up post, where I explain how I researched and analysed texts for this post, as well as my own position and research background... and what this all has to do with Quirkos, given that we make qualitative analysis software.

I hope this post has been helpful in offering a sample of what post qualitative inquiry can look like, as well as the many nuances to consider when you're doing post qualitative research. Regardless of whether you would like to proceed with post qualitative inquiry or not, you may like to check out our curated course on qualitative research (even just as a helpful contrast to what you're doing).

References and further reading

Aagaard, J. (2022). Troubling the Troublemakers: Three Challenges to Post-Qualitative Inquiry. International Review of Qualitative Research, 15(3), 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/19408447211052668

Bhattacharya, K. (2021). Rejecting Labels and Colonization: In Exile From Post-Qualitative Approaches. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420941049

Gerrard, J., Rudolph, S., & Sriprakash, A. (2017). The Politics of Post-Qualitative Inquiry: History and Power. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(5), 384–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416672694

Gildersleeve, R. E. (2018). Laziness in Postqualitative Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(9), 694–703. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417744579

Koro, M. (2021). Post-Qualitative Projects: Exhilarating and Popular “Fashion”? Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420932600

Kuecker, E. (2021). Labors of Reading in Post Qualitative Inquiry. International Review of Qualitative Research, 13(4), 540–554. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940844720939062

Lester, J. N. (2020). Relational Engagements With Post-Qualitative Inquiry: There Are No Blank Pages. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420931133

Murris, K. (2021). Making kin: Postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist research. In K. Murris (Ed.), Navigating the postqualitative, new materialist and critical posthumanist terrain across disciplines: An introductory guide. Routledge.

Rautio, P. (2021). Post-Qualitative Inquiry: Four Balancing Acts in Crafting Alternative Stories to Live By. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 228–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420933297

St. Pierre, E. A. (2018). Writing Post Qualitative Inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 24(9), 603–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417734567

St. Pierre, E. A. (2021a). Post Qualitative Inquiry, the Refusal of Method, and the Risk of the New. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419863005

St. Pierre, E. A. (2021b). Why Post Qualitative Inquiry? Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 163–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420931142

St. Pierre, E. A. (2023). Poststructuralism and Post Qualitative Inquiry: What Can and Must Be Thought. Qualitative Inquiry, 29(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778004221122282

Truman, S. (2019). Feminist New Materialisms. In Atkinson et al. (Eds.) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Research Methods. SAGE Publications.

Wolgemuth, J. R., Marn, T. M., Barko, T., & Weaver-Hightower, M. B. (2022). Radical Uncertainty Is Not Enough: (In)Justice Matters of Post-Qualitative Research. International Review of Qualitative Research, 14(4), 575–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/19408447211012658