Applying feminist theory to qualitative research: intersectionality, reflexivity and social justice

Knowing a range of theoretical frameworks can help you examine your qualitative data through a new lens. So, I invite you to keep reading even if you don't consider yourself a 'feminist researcher'.

This post will talk about some important concepts in feminist research and how to apply them to qualitative methods. Feminist theory is useful for any scholar studying complex social dynamics and experiences - so if you're doing qualitative research, you can benefit from adding a feminist framework to your toolkit.

What is feminist research?

Feminist research explores how systems of social power produce inequities in society. It explores a wide range of social systems (such as gender, class, race), but retains a primary aim to empower women (Hawkey and Ussher, 2022). Research institutions often reproduce misogynistic ideas even in 'empirical' and 'scientific' research (Lokot, 2021). So feminist research aims to redress this balance, generating new knowledge that actually accounts for women and others who are marginalised under the current gender system (Hawkey and Ussher, 2022). Feminist research has the goal of producing positive social change: by directly informing policies and activism, or by empowering participants by giving them an opportunity to share their gendered experiences (Kingston, 2020).

Feminist standpoint: looking askance at power?

Feminist studies aims to address scholarly biases that reinforce patriarchal ideals. In the 1970s and 1980s, many feminists saw qualitative research as a way to radically overhaul scientific enquiry. They saw it as well-placed to undercut positivist approaches, instead privileging individual perspectives (Kingston, 2020, Hawkey and Ussher, 2022).

Standpoint theory developed from this era of feminism as a way to get the most nuanced critique of social power imbalances. According to standpoint theory, marginalised people possess a clearer perspective on power, as they have direct experience of disempowerment. This provides an intimate perspective on the inner workings and contradictions of disempowering ideologies (such as institutionalised misogyny and racism), which is crucial for developing revolutionary social critiques (Sweet, 2020, O'Shaughnessy and Krogman, 2012).

While standpoint is quite an old theory, it continues to be used as a framework for feminist qualitative research. It's a compelling justification for qualitative methodologies: facilitating deep analysis of complex social inequalities that may appear erroneously like "common sense", if they are approached from a more privileged position. Later iterations on the theory have nuanced its approach, and dropped 'feminist' from its name (Hawkey and Ussher, 2022) – to acknowledge the value of a wide range of standpoints and subject positions than just those created by gender.

Intersectional feminism in qualitative research

While feminist research focuses on gender politics, it does not narrowly reduce all social interactions to power dynamics between women and men. It's reductionist to consider social dynamics solely through the lens of (binary) gender. This defeats the object of conducting a qualitative study to highlight the full complexity of your subject. It also creates a monolithic category of "women" that isn't helpful in describing diverse experiences of womanhood.

Intersectional approaches originated in black feminism to counter feminist theories which prioritised and overgeneralised white womanhood. By considering an individual's unique overlap of social identities rather than just their gender alone, intersectionality provides a more complete picture of their position in society and the problems they may encounter (Crenshaw, 1991; Hamilton, 2020). An intersectional feminist approach may consider race, transgender/non-binary subject positions, sexuality, disability and class, among many others. Intersectionality works well combined with qualitative methodologies such as constructed grounded theory, as both draw on complexity and specificity as a source of analytical rigour (Kassam et al, 2020).

Reflexivity, ethics and participatory action in feminist qualitative research

Feminist qualitative research examines the power and position of the researcher. Many positivist 'empirical' studies fail to consider how the researcher's social position may affect the results. So feminist research seeks to counter this through championing reflexivity, the idea that researchers should be consciously aware of their role in producing knowledge (Lokot, 2021).

Closely related is the concept of positionality: considering how your own identity or position of power may influence your research. This allows you to more clearly account for the power dynamic between you, your participants and your institution (Hamilton, 2020). Researcher positionality isn't just a laundry list of identity labels in your paper introduction, but should be a continual conversation with yourself during the research process (Sweet 2020). The goal isn't to cut yourself out of the research - an impossible task - but to acknowledge that your perspective will contribute to your analytical conclusions.

This addresses the problems of so-called 'empirical' research, which often elevates the researcher and assumes they have a unique capacity to be objective, omitting alternative perspectives and marginalised voices (Lokot, 2021). Reflexivity and positionality provide room for perspectives beyond those of the researcher, because they question the elevation of objectivity and the assumed authority of the patriarchal research institution (Lokot, 2021; Hamilton, 2020). Through taking a reflexive approach, the objective of research can become more clearly for the benefit of research participants rather than an authoritative perspective about them as Othered subjects (Hawkey and Ussher, 2022; Lokot, 2021).

Feminist research also considers the ethical complexities of the researcher/participant relationship and of studying social inequalities (O'Shaughnessy and Krogman, 2012). For example, if participants are relating traumatic experiences of social marginalisation, this carries the risk of harm. They might regret what they share later, especially if they misapprehend the purpose of the study (which may be concealed from them to avoid influencing the results). They may then be surprised by the emotional toll of participating, or regret contributing if they fear the repercussions of speaking out about their experiences. Depending on their familiarity with feminist frameworks, it may also be jarring if the researcher recontextualises their trauma as an example of structural oppression (Watts, 2006). Equally, the long-term benefits of giving people a lens to identify and challenge the social injustices they face may outweigh the short-term discomforts.

One way to address both research ethics and power imbalances is to use participatory methods, to involve participants more directly in the research process. Traditional methods may allow participants to control how their data is collected or choose their own pseudonym. But participatory action research allows participants to play a much more active role in the design and execution of the research, as equal collaborators (Lokot, 2021). This prioritises their agency and empowerment, and reduces the impact of the researcher's bias and positionality. This is a particularly compelling method for feminist studies as it directly challenges the power imbalance of traditional research methods, developing more equitable and less exploitative systems of knowledge (Kingston, 2020).

Is feminist research inherently qualitative?

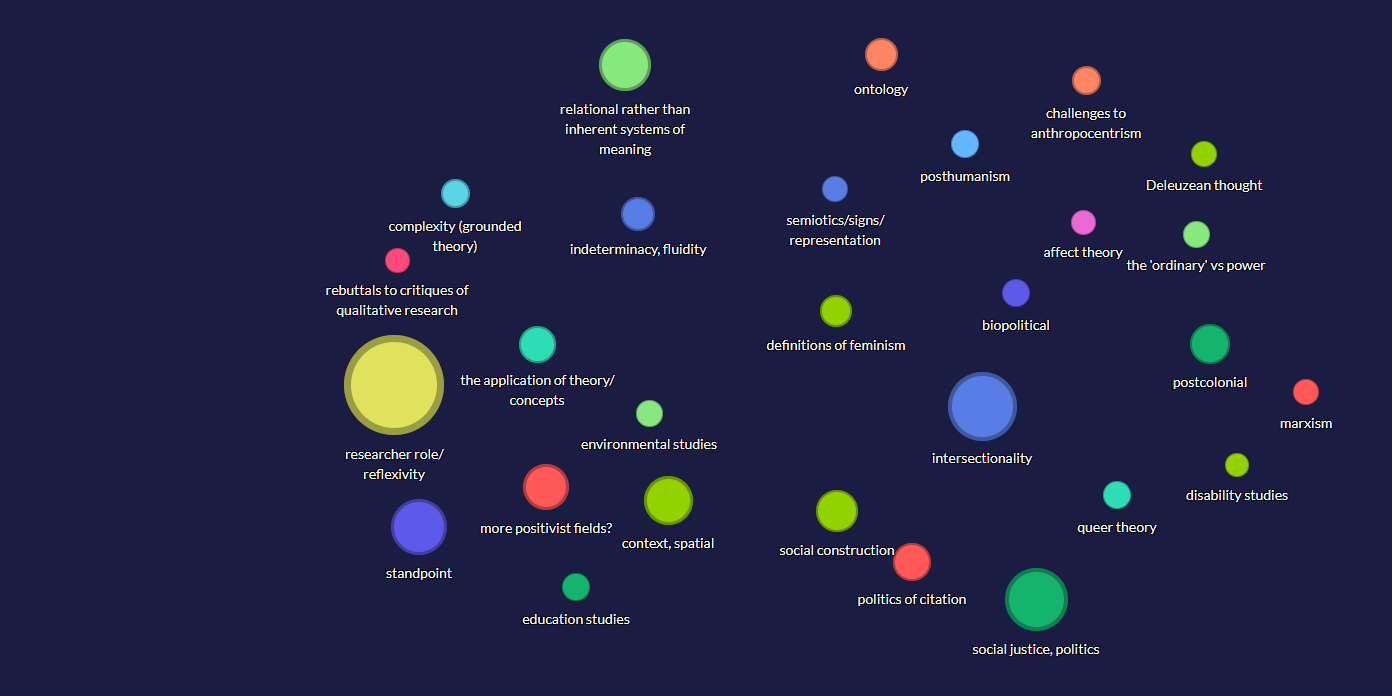

The theories summarised in this post have a curious geography to them. Social context is given a spatial reality through 'positionality', 'intersections', and 'standpoint'. We could say that feminist theory examines exterior phenomena that may then represent themselves 'internally' on people's histories and experiences. But this boundary between interior/exterior is quite unstable – they determine one another iteratively rather than one imposing itself on the other. I think this is why feminist theory goes so well with qualitative approaches like critical discourse analysis, which is attuned to the social context and power dynamics that structure everyday speech.

Qualitative research is often seen as a 'given' or an 'ideal' methodology for feminist studies. Equally, empirical and positivist feminist research has an important role in highlighting material inequalities, like gender wage gaps (O'Shaughnessy and Krogman, 2012). But a positivist, quantitative analysis risks being folded into the patriarchal system because it's forced to play by the same rules. For instance, some people suggest that gender wage gaps are not proof of economic discrimination, but instead that women are simply more inclined to choose worse-paying occupations. This ignores the structural discriminations that may result in women making this choice, as well as recent increases in the representation of women in previously underrepresented sectors and job types, which hasn't resulted in an equivalent increase in wage equality (e.g. see Gharehgozli and Atal, 2020, or Kunze, 2018). But this 'counterpoint' remains a misogynistic talking point all the same, and shows the importance of taking both qualitative and quantitative data into account.

Mixed methods are one way to navigate this methodological dilemma, allowing quantitative and qualitative methods to enhance and nuance one another (O'Shaughnessy and Krogman, 2012). But overall, there is no singular answer on how best to drive positive social change within a patriarchal academic institution - it's up to you as a researcher. It's difficult to do research for social justice when you're embedded in an institution that doesn't necessarily have your aims or your participants' best interests in mind. Taking a feminist lens to your work will help you identify and reflect on these tensions when they arise, strengthening your work and the social impact it can have.

As feminism is an incredibly broad field, I didn't go into every single nuance of feminist theory in this post. The best way to engage with feminist theory is to read it directly, and I provide some starting points in the recommended reading below. The influence of social constructivism on feminism is its own post, at least - but if social construction is your cup of tea (it certainly is mine!), you might be interested in our blog post on discourse analysis.

I will be writing more blog posts focused on applying theory in qualitative analysis, so stay tuned and subscribe to our blog if you'd like to hear more from us!

Sources for this post

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Gharehgozli, O., & Atal, V. (2020). Revisiting the gender wage gap in the United States. Economic Analysis and Policy, 66, 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.04.008

Hamilton, P. (2020). ‘Now that I know what you’re about’: Black feminist reflections on power in the research relationship. Qualitative Research, 20(5), 519–533. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119891583

Hawkey, A. J., & Ussher, J. M. (2022). Feminist research: Inequality, social change, and intersectionality. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research Design. SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781529770278

Kassam, S., Marcellus, L., Clark, N., & O’Mahony, J. (2020). Applying Intersectionality With Constructive Grounded Theory as an Innovative Research Approach for Studying Complex Populations: Demonstrating Congruency. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 160940691989892. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919898921

Kingston, A. K. (2020). Feminist Research Ethics: From Theory to Practice. In R. Iphofen (Ed.), Handbook of Research Ethics and Scientific Integrity (pp. 531–549). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-16759-2_64

Kunze, A. (2018). The Gender Wage Gap in Developed Countries. In S. L. Averett, L. M. Argys, & S. D. Hoffman (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Women and the Economy (pp. 368–394). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.11

Lokot, M. (2021). Whose Voices? Whose Knowledge? A Feminist Analysis of the Value of Key Informant Interviews. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 160940692094877. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920948775

O’Shaughnessy, S., & Krogman, N. T. (2012). A Revolution Reconsidered? Examining the Practice of Qualitative Research in Feminist Scholarship. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 37(2), 493–520. https://doi.org/10.1086/661726

Sweet, P. L. (2020). Who Knows? Reflexivity in Feminist Standpoint Theory and Bourdieu. Gender & Society, 34(6), 922–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243220966600

Watts, J. (2006). ‘The outsider within’: Dilemmas of qualitative feminist research within a culture of resistance. Qualitative Research, 6(3), 385–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106065009

Recommended reading

Ahmed, S. (2017). Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press.

Beauvoir, S. (1949). The Second Sex. Vintage.

Braidotti, R, (1994). Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. Columbia University Press.

Butler, J. (1990), Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. (2017). On Intersectionality: Essential Writings. The New Press.

Davis, A. (1981). Women, Race, & Class. Vintage.

Haraway, D. (1988). Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

hooks, b. (1984). Feminist theory: from margin to center. Routledge.

Lorde, Audre (1984). Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Random House.

McLaren, M. A. (Ed.) (2017). Decolonizing Feminism: Transnational Feminism and Globalization. Rowman & Littlefield.

Mohanty, C. T. (2003). Feminism without Borders: Decolonizing Theory, Practicing Solidarity. Duke University Press.